The opening scenes of Milton Friedman’s popular TV series, Free to Choose, feature panoramic harbor views of Hong Kong, his favorite economy. In his telling, the city was a neoliberal economic “utopia.”

That was never quite true, but there’s little disagreement about the key elements that underpinned its ascent from a “barren rock” to a glittering metropolis: Free markets and free speech.

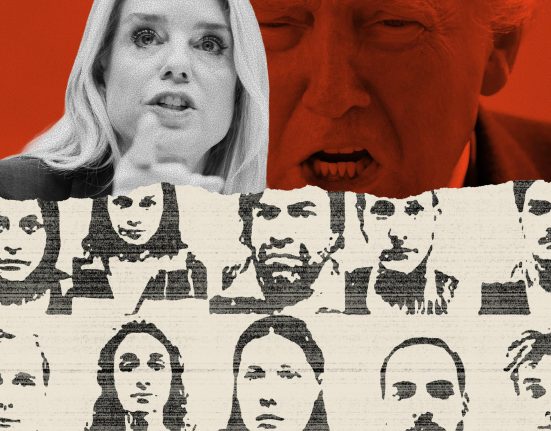

Nobody embodied that combination more than the clothing entrepreneur-turned-publisher Jimmy Lai, Friedman’s close friend, who was jailed for 20 years this month for his pro-democracy efforts in the pages of his now-shuttered Apple Daily. His is the most high-profile of a series of arrests and imprisonments under a draconian National Security Law imposed by Beijing.

Films have been censored, and theater plays axed. Books dealing with topics sensitive in China, like the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre, have gone missing from college libraries. The University of Hong Kong requires library users to register before they can gain access to certain titles, now housed in a “Special Collections” section. The Hong Kong Foreign Correspondents Club — which itself made no comment about Lai’s sentencing — found that two-thirds of its journalist members routinely self-censor.

There’s no question that the city’s operating model has fundamentally changed. As Lai discovered, the rules that once governed one of the world’s greatest success stories — and that drew Friedman’s unqualified admiration — have changed: The markets are still free, but speech can be costly.

Global investors, however, seem unfazed. The stock market is booming, largely as a conduit for Chinese companies going global, and handily outperformed the S&P 500 last year. Indeed, on the day Lai was sentenced, the Hang Seng Index jumped another 1.8%.

This is, to put it mildly, strange. It would be naive to think that Hong Kong’s clampdown on speech won’t affect its long-term prospects. The free flow of information is the lifeblood of the world’s third largest financial center, after New York and London, and Apple Daily — for all its lurid crime stories and salacious gossip — was among a litany of outlets holding government officials to account. Famously, it reported on the purchase of a Lexus by a former financial secretary shortly before he introduced a tax on luxury vehicles. That story would likely never appear today.

In the financial world, analysts have gone underground to avoid getting into trouble, according to Bloomberg; to discuss the news, some huddle with clients in private WeChat rooms, although even in those spaces they censor themselves, or speak in euphemisms because WeChat is monitored by Chinese authorities. The number of publicly available research reports has dwindled. Some analysts use burner phones.

Global business consultancies with offices in Hong Kong tread cautiously when advising clients about the National Security Law, which claims extraterritorial reach: Speech anywhere in the world deemed unacceptable by Hong Kong’s national security apparatus — a Beijing-controlled state-within-a-state — can be prosecuted in the city.

Domestically, all kinds of dissent can be deemed a security threat. After a huge fire ripped through a housing estate last year, killing at least 146 residents, angry citizens demanding government accountability for the tragedy were branded agents of “hostile foreign forces” seeking to destabilize society. Several were arrested.

To be sure, Hong Kong still has formidable advantages as a haven for capital. It’s on track to overtake Switzerland as the leading global center for private wealth management, and American multinationals continue to pile in: 42 set up or expanded in the city last year.

That’s perhaps not too surprising: Hong Kong retains the low tax regime and light regulatory touch that Friedman so admired. But the city has become a testing ground for his thesis that a lack of political freedom will, eventually, undermine the markets.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this