Far beyond our solar system, in the distant Pegasus constellation, lies a star system that is reshaping our understanding of planetary formation. HR 8799, located 129 light-years away, is home to a rare group of super-Jupiters, gas giants that are much larger than our own Jupiter. These planets, orbiting far from their star, present a unique opportunity to study the early stages of planetary evolution. With their massive size and extreme conditions, they serve as natural laboratories for astronomers to explore how planets form and develop in ways that could eventually illuminate the mysteries of other distant worlds, including those that may resemble Earth.

A Unique System of Super-Jupiters

The HR 8799 system stands out for its unusual collection of four massive gas giants, making it one of the most remarkable planetary systems observed. The planets range in mass from five to ten times that of Jupiter, with their orbits situated much farther from their star compared to the gas giants in our own solar system. This arrangement offers an intriguing glimpse into the early stages of planet formation.

“HR 8799 is somewhat unique because, thus far, it’s the only imaged system with four massive gas giants, but there are other known systems with one or two even larger companions and whose formation remains unknown,” said Dr. Jean-Baptiste Ruffio, an astronomer at the University of California, San Diego.

The HR 8799 system has provided astronomers with a rare opportunity to study gas giants directly using advanced observational methods, unlike most exoplanet discoveries that are inferred from indirect data.

Credit: Nature Astronomy

The ability to observe such distant planets directly allows scientists to examine their atmospheric compositions in greater detail. In the case of HR 8799c, d, and e, astronomers have used the unprecedented sensitivity of the Webb Telescope to detect hydrogen sulfide gas, marking a major milestone in exoplanetary research.

Understanding the Chemical Composition of Super-Jupiters

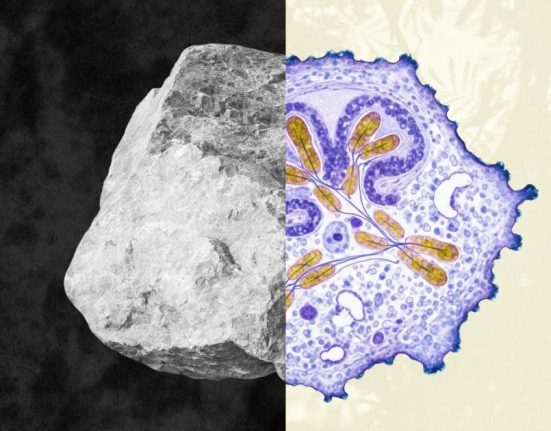

The detection of hydrogen sulfide is a breakthrough that sheds light on the chemical processes involved in planet formation. Unlike carbon and oxygen, which are often found in both solid and gaseous forms within protoplanetary disks, sulfur presents a unique case.

“Carbon and oxygen in these planets have been studied from Earth-based observations in the past, but they’re not good signatures for solid matter because they can come from both ice or solids in the disk, or from gas,” explained Dr. Jerry Xuan, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles and Caltech.

“But sulfur is unique because at the distance these planets are from their star, it has to be in the solids,” Dr. Xuan continued. This finding suggests that the sulfur in the planets’ atmospheres must have originated from solid material in the planets’ birth disk, rather than being accreted as gas. As the planets formed and their cores heated up, solid materials were vaporized, releasing sulfur into their atmospheres, where it is now detectable.

This discovery of hydrogen sulfide also implies that the process of planetary accretion, whereby planets gather material from their surrounding environments—may be more uniform across different systems than previously thought. The ratios of sulfur, carbon, and oxygen in these planets are strikingly similar, hinting at a universal process of heavy element enrichment.

Implications for the Search for Earth-Like Planets

One of the most exciting implications of this discovery is the potential to apply these techniques to study other exoplanets, including Earth-like ones. While the current study is limited to gas giants, the ability to visually and spectrally separate the planet from its star opens up new possibilities for future exoplanet studies. As Dr. Xuan noted,

“The technique applied here, which lets researchers visually and spectrally separate the planet from the star, will be useful for studying exoplanets at great distances from Earth in clear detail.”

The method, though currently limited to gas giants, is expected to be applicable to smaller, Earth-like planets in the future. “Finding an Earth analog is the Holy Grail for exoplanet search, but we’re probably decades away from achieving that,” Dr. Xuan added. However, with technological advancements in telescopes and instruments, scientists hope to eventually study the atmospheres of Earth-like planets and search for biosignatures such as oxygen and ozone.

According to the study, published in Nature Astronomy, this technique represents a significant leap forward in exoplanetary science. “But maybe in 20-30 years, we’ll get the first spectrum of an Earth-like planet and search for biosignatures like oxygen and ozone in its atmosphere,” Dr. Xuan said, emphasizing the long-term potential of these discoveries.

A Broader Understanding of Planetary Formation

The findings from this study add to our growing understanding of how planets form and evolve. The uniform enrichment of elements like sulfur, nitrogen, and oxygen in the HR 8799 planets suggests that the process of accretion, where these elements are gathered from the surrounding disk, is a natural part of planet formation. This pattern has been observed in our own solar system’s gas giants, Jupiter and Saturn, and it appears to be a universal feature of planet formation.

“It’s not easy to explain the uniform enrichment of carbon, oxygen, sulfur and nitrogen for Jupiter, but the fact that we’re seeing this in a different system is suggesting that there’s something universal going on in the formation of planets, that it’s quite natural to have them accrete all heavy elements in nearly equal proportions,” Dr. Xuan concluded. This discovery could lead to new insights into the processes that shape not only gas giants but also smaller, potentially habitable planets.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this