In places like Chernobyl and Fukushima, where nuclear disasters have flooded the environment with dangerous radiation, it makes sense that life might evolve ways to survive it.

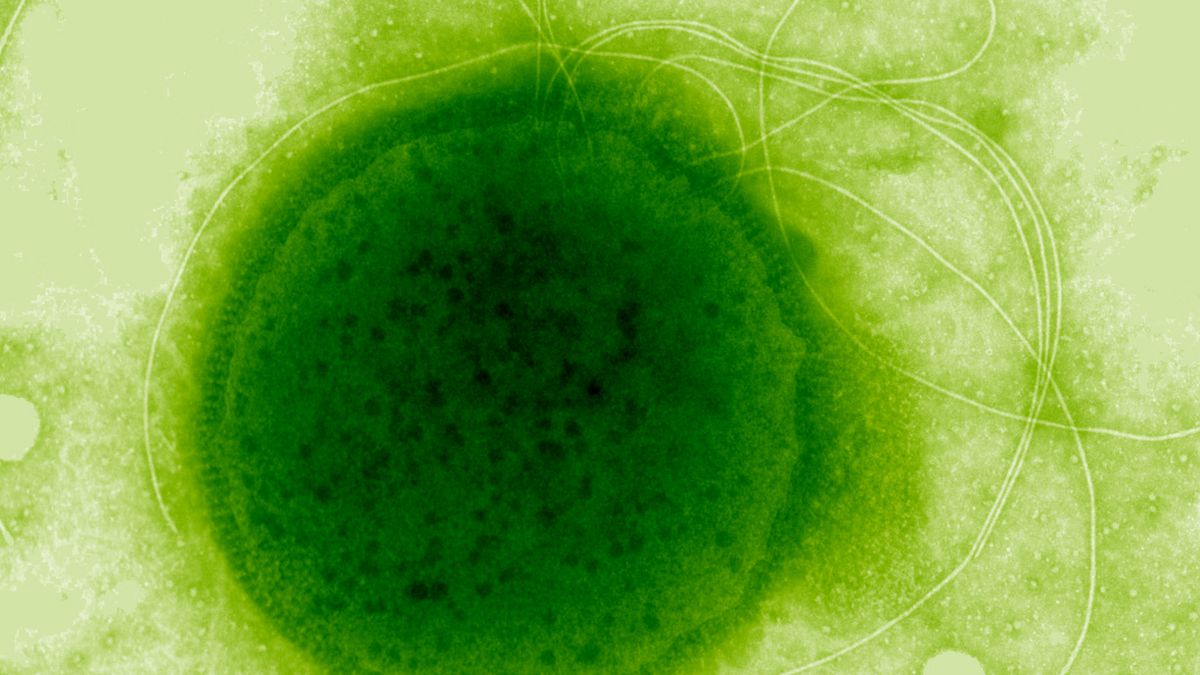

But one of the most radiation-resistant organisms ever discovered doesn’t come from anywhere radioactive at all. An archaeon called Thermococcus gammatolerans is able to withstand an extraordinary radiation dose of 30,000 grays – 6,000 times higher than the full-body dose that can kill a human within weeks.

In the Guaymas Basin in the Gulf of California, around 2,600 meters (8,530 feet) beneath the ocean’s surface, hydrothermal vents spew superheated, mineral-rich fluids into the surrounding darkness. It’s there that T. gammatolerans makes its home, far from any human structure – never mind a nuclear reactor.

The Guaymas hydrothermal field is a region where the ocean floor cracks open, allowing volcanic heat and chemistry to surge into the water.

Between the crushing pressure of the water at lightless bathypelagic depths and the extreme heat, these environments are dazzlingly inhospitable to humans. It is only natural that we want to know how the heck life manages, not just to survive, but to thrive in such a place.

T. gammatolerans was first discovered decades ago, when scientists used a submersible to collect a sample of the microbes living on a hydrothermal vent.

Back in the lab, a team led by microbiologist Edmond Jolivet of the French National Center for Scientific Research exposed enrichment cultures to 30,000 grays of gamma radiation from a cesium-137 source. One species in particular continued to grow, even after irradiation at an incredible 30,000 grays.

That species turned out to be a previously undescribed archaeon, named T. gammatolerans. It had quietly been living its best life attached to Guaymas vents, harboring a resistance to a peril to which it would hardly have been exposed.

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>

frameborder=”0″ allow=”accelerometer; autoplay; clipboard-write; encrypted-media; gyroscope; picture-in-picture; web-share” referrerpolicy=”strict-origin-when-cross-origin” allowfullscreen>That’s not to say that it can’t handle peril. T. gammatolerans thrives at temperatures around 88 degrees Celsius (190 degrees Fahrenheit) and feeds on sulfur compounds. But radiation resistance didn’t seem to be a survival necessity in the microbe’s habitat. Before Jolivet and his team introduced their cesium-137 source, radiation simply wasn’t part of the equation.

The mystery deepened with a 2009 paper that looked into the genome of T. gammatolerans. A team led by microbiologist Fabrice Confalonieri of the University of Paris-Saclay in France was expecting to find a larger-than-usual proportion dedicated to protection and repair. However, they found no obvious excess of DNA repair machinery; T. gammatolerans‘ kit was surprisingly normal.

So, if the answer wasn’t in the microbe’s DNA, perhaps it could be found in the damage itself. In a 2016 paper, a team led by chemical biologist Jean Breton of Grenoble Alpes University investigated exactly what ionizing radiation does to T. gammatolerans, and how the microbe responds.

The researchers exposed colonies of the archaeon to gamma radiation from a cesium source at doses up to 5,000 grays and recorded the results. Their experiments showed that gamma rays do still harm T. gammatolerans‘ DNA – this microbe is not invincible – but the oxidative damage caused by the free radicals set loose by radiation was significantly lower than expected.

In addition, much of that damage had been repaired within an hour, with repair enzymes standing by for rapid action.

While we still don’t know exactly why T. gammatolerans is so effective at limiting and repairing radiation damage, scientists suspect its habitat plays a role. Life at hydrothermal vents means constant exposure to extreme heat, chemical stress, and reactive molecules – conditions that can also damage DNA.

Related: Extreme ‘Fire Amoeba’ Smashes Record For Heat Tolerance

The systems that help the microbe survive boiling, oxygen-free darkness may also protect it from ionizing radiation. The evolutionary pressures that shaped T. gammatolerans for life in hydrothermal vents may have also yielded, as a byproduct, the remarkable ability to withstand radiation at doses that would kill much larger organisms.

T. gammatolerans is not a radiation specialist; it has no reason to be. It’s unlikely that, over millions of years in the deep sea, it experienced the kind of sustained, intense radiation that would have shaped its biology.

In evolution, there’s a concept – survival of the good enough. The systems that allow T. gammatolerans to endure boiling volcanic chemistry at the bottom of the sea were good enough for life at a hydrothermal vent.

That they also make it astonishingly resistant to radiation is one of those rare moments when “good enough” turns out to be extraordinary.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this