When asked about Heathcliff’s background in the fourth chapter of Wuthering Heights, the housekeeper Nelly Dean resorts to ornithology. “It’s a cuckoo’s,” she replies, adding that Hareton Earnshaw, the young man who is the rightful heir to Wuthering Heights, has been cheated out of his claim by Heathcliff “like an unfledged dunnock.”

The filmmaker Emerald Fennell, who released her adaptation of Emily Brontë’s haunting 1847 novel last week, knows a thing or two about cuckoos. The protagonists of her previous two movies are also outsiders who wriggle into situations where they would otherwise be uninvited, to the detriment of those they deceive. In 2020’s Promising Young Woman, Carey Mulligan spends her evenings pretending to be wasted at bars and nightclubs to humiliate the men who try to take advantage of her. Saltburn, from 2023, similarly features Barry Keoghan in the role of an unassuming Oxford University student who pulls a Talented Mr. Ripley on the clueless aristocrats who take him in for the summer.

As others have noted, the 40-year-old Fennell has made a name for herself as a director who approaches her projects with distinctively millennial flair. Promising Young Woman is a dark #MeToo comedy saturated with millennial pink, while Saltburn’s murderous plot is set to a soundtrack studded by Arcade Fire, MGMT, Sophie Ellis-Bextor, and other indie hitmakers from the early 2000s. With its striking visual allusions to Gone with the Wind and Harlequin romance paperbacks, Fennell claims that her take on Wuthering Heights is trying to capture the psychological experience of reading the novel for the first time as a 14-year-old girl. But like so many who came of age with the internet, Fennell’s perspective seems shaped less by Barbara Cartland than by the millennial normalization of kink and the cringe-inducing amateur erotica that turned FanFiction.net into a cultural juggernaut at the turn of the century. Because for all its whips, chains, and back sweat, the most offensive part of Fennell’s Wuthering Heights isn’t that it’s transgressive. It’s that it’s shockingly and undeniably boring.

As originally conceived by Brontë, Wuthering Heights is a gothic saga centered on two landowning families—the Earnshaws and the Lintons—who live in a remote corner of the Northern English moors in the late 18th century. Much of the novel’s plot is driven by the doomed love story between the “half-savage” Catherine Earnshaw and the equally fiery Heathcliff, her adopted brother, whose parentage and ethnic background Brontë leaves intentionally vague.

Dealing with themes of intergenerational abuse, addiction, classism, and horror, Wuthering Heights is a difficult book populated with violent, selfish people and anguished ghosts. When I finished reading it for the first time as a teenager, I remember shoving my copy under my bed instead of returning it to my bookshelf; the unsettled feeling that I had read something fundamentally obscene lingered in my bones for days.

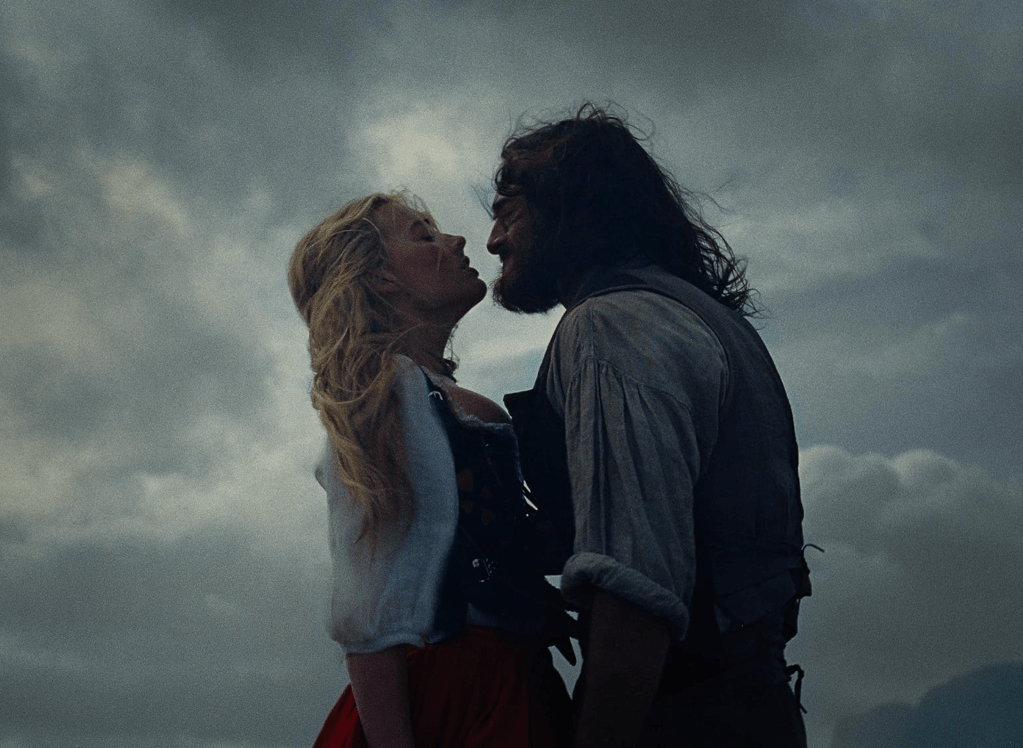

For this reason, I have not sympathized much with fans of the novel who have been making a lot of hay over the aesthetic liberties Fennell has taken in her adaptation, which features the stunning Margot Robbie in the role of Catherine and Jacobi Elordi as Heathcliff, still flush with Byronic air from starring in last year’s Frankenstein. And like that version of Frankenstein, Fennell’s Wuthering Heights is set in a fantastical version of the past, featuring beautifully anachronistic costumes, viscous architecture, and gargantuan, mist-laden crags. It seems Fennell tried to distill the feeling of the uncanny that colors Brontë’s description of the Yorkshire moors, and it largely works; her Alice-in-Wonderland take on Wuthering Heights’ setting accentuates the sense of isolation that both enlivens and immiserates its characters.

Unfortunately, the energy Fennell pours into her worldbuilding is absent from her characters. Her adaptation cuts Hareton and Cathy Linton, the daughter Catherine has with her husband, Edgar Linton, out of the plot entirely. Her version of the housekeeper Nelly is a frigid and inscrutable automaton, and Edgar is so foppishly spineless it’s a wonder that he can even hold himself upright, let alone prove a rival to Heathcliff. In the movie, Catherine’s father assumes the role of the dissipated patriarch that otherwise belongs in the novel to Hindley Earnshaw, Catherine’s alcoholic brother and Hareton’s father. Perhaps Fennell wanted to rein in the actor budget. But this decision muddles Heathcliff’s motivations: In the novel, Mr. Earnshaw’s preference for Heathcliff over Hindley informs the former’s unshakable pride and the latter’s resentment. Upon becoming master of Wuthering Heights, Hindley turns Heathcliff into a servant, leaving Heathcliff degraded, unmarriageable, and vengeful.

On the other hand, Fennell gives Wuthering Heights’ Joseph what has to be the most legendary glow-up in the history of literary adaptations. She transmutes Brontë’s aged, bitter, Bible-thumping servant, whose transcribed Yorkshire accent has been giving high schoolers migraines for generations, into a young, suave, and perfectly intelligible BDSM enthusiast. When I watched the scene where Joseph pulls his shirt off before performing an unspeakable act on a fellow servant while spied on by Catherine and Heathcliff, I audibly guffawed. Then and there, I knew that Fennell had chosen the easy way out.

“Wuthering Heights” (those quotes are Fennell’s) opens with the sounds of a man moaning in what you are supposed to guess is a sexual act, before the title card cuts to a shot of a criminal’s hanging. This bait and switch over la petite mort is intriguing at first; a pointed reference to a thin line between death and desire that Brontë weaves carefully into her novel. But wait, Fennell says, I just don’t think we’ve worked that metaphor through quite enough. So instead of allowing Catherine and Heathcliff’s self-destructive tendencies to manifest themselves through the demonic scenes of mental breakdown that scream out of the novel, she instead decides that they will spend half of the film sucking on each other’s fingers (among other things).

The result of all this subtext-made-text is dreadfully dull. I started checking my phone by about the third or fourth scene depicting Catherine and Heathcliff getting hot and heavy, with little protest from Edgar. And while it’s true that other film and TV versions of Wuthering Heights have depicted Catherine and Heathcliff in a physical relationship, this is the first where Edgar’s impotence has removed all sense of real conflict from Brontë’s sordid love triangle. So much for all the “yearning” the film promised in its ad campaign.

Whether she realizes it or not, Fennell is using the mild shock of sexual deviance to tell us about Wuthering Heights’ inherent masochism instead of having the courage to show us the novel’s seductively ugly heart. Heathcliff as written by Brontë is a cruel man who strangles dogs and speaks placidly about beating women. Whether he’s of Roma, Irish, or African descent, he has no trouble functionally enslaving Hareton, Catherine’s daughter, and even his own son as part of his revenge plot against the Earnshaws and Lintons (none of which is included in the movie). Meanwhile, Catherine at one point in the novel shakes baby Hareton so violently for crying that she drives Edgar to intervene, only to slap him for intruding. She claims she would rather be cast out of heaven than leave Wuthering Heights and its grounds, and condemns Heathcliff to be haunted by her ghost despite having rejected him first.

The only moment in the film where Fennell gives us a real glimpse of the brutal spirit that animates both characters is in a scene where they mercilessly harass Isabella Linton over the feelings she has developed for Heathcliff. But once again, Fennell sublimates even this famously problematic relationship into a banal BDSM arrangement with Heathcliff—and it’s okay, because Isabella is actually pretty into it, and Heathcliff asked for her consent anyway. In the novel, Heathcliff skewers Isabella in the neck with a dinner knife, but Fennell seems convinced that even in our pornified age, hers is the more provocative interpretation.

There is a version of “Wuthering Heights” where Robbie and Elordi’s disarming charm, set against Fennell’s shots of creeping slugs, leering puppets, disemboweled pigs, and other grotesque imagery, forces viewers to look squarely at the alluring narcissism that joins Catherine and Heathcliff together. After all, Brontë’s project was to consider, in a manner that avoided easy moralizing, the Romantic provocation that a life given over to the natural passions is better than one governed by reason and restraint, particularly in a bleak and unjust world. By writing such toxic and yet magnetic protagonists, she poses a dilemma. A teenager might read such lines from Catherine as “he’s more myself than I am” and “whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same” and feel a thrill. But for anyone who has experienced real love—or at least read some other novels—those same words frighten as much as they excite. For all their fervor, they solipsistically deny the careful appreciation of the particular and the desire for mutual growth that sustains a love that nurtures rather than consumes.

The braver and more interesting choice would have been for Fennell to interrogate the unsettling implications of a culture where such a vicious relationship is billed as “the greatest love story of all time.” But she instead indulges the adolescent impulse to defang Brontë’s immortal characters, and then lies to herself about having done so by fitting them with plastic vampire teeth.

Then again, maybe Fennell is just having a laugh at our expense. If you want to watch a spiritually faithful adaptation of Wuthering Heights, complete with sexually charged graveyard visits, a decades-long real estate scheme, and uh, yearning in spades, Saltburn is already that movie. It’s hard not to suspect that Fennell, in her clever and cynical way, just wanted to see if she could get away with turning fantasy casting plucked from the recesses of Tumblr into a major motion picture. Because the only other explanation I can conjure for the gooey mess that is “Wuthering Heights” is that Fennell doesn’t realize her promising artistic vision has been cuckooed by something all too ordinary instead.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this