Participants

Participants in our experiment were recruited by YouGov—a professional online polling firm with a large panel of respondents in the United States. All study participants gave their informed consent to participate. Participants were included in the study only if they self-reported using X at least several times a month. The sample is 78% white, 52% male and relatively well educated, with 58% having completed at least 4 years of university. In terms of political affiliation, 46% identify as Democrats and 21% as Republicans. Among the participants, 66% use X at least once a day and 94% at least once a week. As for posting activity, 27% post at least once a day and 53% at least once a week. See Supplementary Information section 1.4 for detailed summary statistics and the comparison of our sample with Twitter users from the nationally representative Social Media Study by the American National Election Studies.

Experimental design

Participants were randomized into an algorithmic or chronological feed for the duration of the experiment in exchange for compensation. Supplementary Information section 1.2 provides information on the compensation scheme and on how different elements of the experiment appeared on the X platform.

The randomization procedure was effective: participants assigned to different feed conditions exhibited no systematic differences in demographic characteristics or social media usage beyond what would be expected by chance. The only notable imbalance relates to the initial feed setting. The proportion of participants who were already using the algorithmic feed at baseline was two percentage points higher among those assigned to the algorithmic group (77% compared with 75%). All analyses account for the initial feed setting. Supplementary Information section 1.7 provides further details on balance and reports summary statistics by treatment group and initial feed setting.

Data on outcomes

Outcome data on attitudes come from the post-treatment survey. The coding of the survey-based outcome variables is presented in Supplementary Information section 1.3. To analyse the content of users’ feeds and the accounts they follow, we applied natural language processing methods. The Llama 3-based classification of feed content, collected using a Google Chrome extension, categorizes posts by political leaning—either conservative or liberal—and by type, distinguishing between posts from political activists, entertainment accounts and news media outlets. Details are provided in Supplementary Information section 1.5. The Llama 3-based classification of followed accounts is based on data collected through users’ X handles. This procedure is described in Supplementary Information section 1.6.

We conduct several validation exercises for the Llama 3 annotations in Supplementary Information sections 1.5 and 1.6. These include comparisons with machine-learning classifiers based on word frequencies, as well as evaluations conducted by human annotators.

ITT effects estimates

Given the experimental design, the ITT effect estimates were obtained by comparing mean outcomes between respondents assigned randomly to the algorithmic feed and those assigned to the chronological feed, conditional on their initial feed setting. Our main specification estimates the effect of switching the algorithm on for users who initially had it off, and switching it off for users who initially had it on. Specifically, we estimate the following model:

$$\begin{array}{l}{Y}_{i}=\alpha +{\beta }_{1}{\rm{I}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}\,{{\rm{C}}{\rm{h}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{o}}}_{i}\times {\rm{T}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{m}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{t}}\,{{\rm{A}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{g}}{\rm{o}}}_{i}+{\beta }_{2}{\rm{I}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}\,{{\rm{A}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{g}}{\rm{o}}}_{i}\\ \,\times {\rm{T}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{m}}{\rm{e}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{t}}\,{{\rm{C}}{\rm{h}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{o}}}_{i}+{\beta }_{3}{\rm{I}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}\,{{\rm{A}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{g}}{\rm{o}}}_{i}+{{\bf{X}}}_{i}^{{\prime} }{\boldsymbol{\Gamma }}+{\varepsilon }_{i}\end{array}$$

(1)

where i indexes respondents. Yi represents outcome variables (for example, post-treatment political attitudes of respondents). Initial Algoi is a dummy variable for the initial feed setting; it equals one for respondents who had been using the algorithmic feed before our intervention and zero for those who had been using the chronological feed. Treatment Algoi is a dummy variable for being assigned to the algorithmic feed setting during the treatment phase; it equals 1 for respondents assigned to the algorithmic feed and 0 for those assigned to the chronological feed. Note that, by construction, Initial Chronoi = 1 − Initial Algoi and Treatment Chronoi = 1 − Treatment Algoi. Xi is a vector of control variables discussed below.

The coefficients of interest are β1 and β2, which estimate the ITT effects of switching the algorithm on and switching it off, respectively. Because we control for Initial Algo, those switching from the chronological to the algorithmic feed are compared with users who initially had the chronological feed and remained on it, whereas those switching from the algorithmic to the chronological feed are compared with users who initially had the algorithmic feed and remained on it.

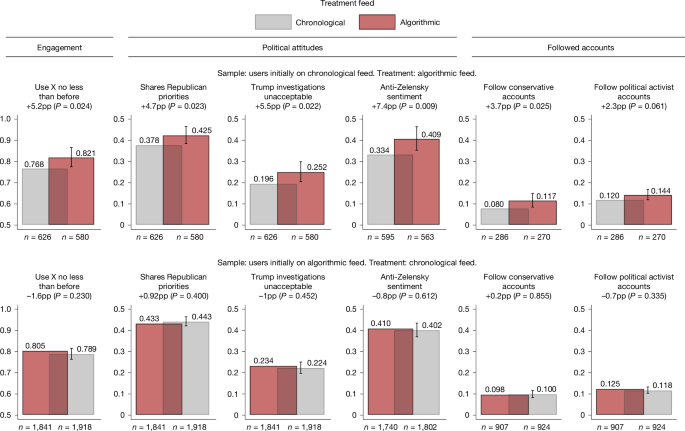

We consistently report two sets of estimates. First, we report unconditional estimates, namely, controlling only for the initial feed setting and, when available, the pre-treatment value of the outcome variable. The unconditional model is justified by the balance in observables across treatment groups. Second, we also report estimates that flexibly control for pre-treatment covariates. Our baseline approach relies on GRFs—a machine-learning method that identifies the most relevant covariates and adjusts for them non-parametrically39. This approach limits the researcher’s discretion in selecting covariates and functional form, including mitigating concerns about model misspecification46. We use the full set of available pre-treatment covariates as input to the GRFs. The covariates include initial feed setting, gender, age, indicators of X use, all categories of educational attainment and race, frequency of X use and posting, political affiliation, the device used to complete the pre-treatment survey (such as a laptop or smartphone), life satisfaction, happiness and affective polarization. Technical details are provided in Supplementary Information section 2.2.1. Baseline ITT estimates are reported in Fig. 2.

Throughout the analysis (in the main text and Extended Data Figs. 4, 5 and 7 and Supplementary Information), we present ITT estimates in graphical form using coefficient plots. Estimates from the unconditional specification are shown in blue, whereas those from the specification controlling for pre-treatment covariates are shown in orange. For clarity, we refer to β1 estimates as ‘Chrono to Algorithm’ and β2 estimates as ‘Algorithm to Chrono’ in these coefficient plot figures.

In Supplementary Information section 2.4, we report results for all outcome variables using a range of linear specifications, progressively adding the following controls to equation (1): demographic characteristics (gender, age, indicators for being white and for high educational attainment), pre-treatment X use (frequency of use, frequency of posting and self-reported purpose of using X), and political affiliation (Republican, Independent, Democrat or other). We also present results from a specification that includes the predicted probability of having an algorithmic initial feed, obtained using LASSO on all pre-treatment characteristics. In addition, we report results from a specification that controls for post-treatment X use. Although post-treatment use is endogenous, robustness to including this control indicates that the estimated effects are not solely driven by changes in X usage.

In Supplementary Information section 2.4, we also present tests for the symmetry of the effects of switching the algorithm on and off. Specifically, we test whether β1 = − β2, and whether 7 weeks of algorithm exposure, induced by treatment assignment for users initially on the chronological feed, leads to outcome levels similar to those of users who were initially on the algorithmic feed and remained on it, that is, whether β1 = β3.

Compliance and LATE estimates

Due to minimal non-compliance with assigned treatments (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Information section 1.8.1), the ITT estimates do not strictly represent average treatment effects. We estimate LATE for compliers, that is, for respondents who adhered to their assigned feed setting, using instrumental variables regressions, with the assigned feed setting used as an instrument for the feed setting actually used.

We define ‘actual’ feed use during the treatment phase using treatment assignments and respondents’ self-reported compliance from the post-treatment survey. Respondents are classified as compliant if they answered ‘always’ or ‘most of the time’ to the question, ‘Did you stick to the assigned feed?’ Based on this, we construct two variables: Actual Algoi and Actual Chronoi.

Actual Algoi equals 1 if respondent i was compliant and assigned to the algorithmic feed, or non-compliant and assigned to the chronological feed, implying they used the algorithmic feed. Conversely, Actual Chronoi equals 1 if the respondent was compliant and assigned to the chronological feed, or non-compliant and assigned to the algorithmic feed. By construction, Actual Chronoi = 1 − Actual Algoi.

We estimate two-stage least squares regressions, with the second stage specified as follows:

$$\begin{array}{c}{Y}_{i}=\alpha +{\gamma }_{1}{\rm{H}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}({\rm{I}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}\,{{\rm{C}}{\rm{h}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{o}}}_{i}\times {\rm{A}}{\rm{c}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{u}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}\,{{\rm{A}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{g}}{\rm{o}}}_{i})\\ \,+\,{\gamma }_{2}{\rm{H}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{t}}({\rm{I}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}\,{{\rm{A}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{g}}{\rm{o}}}_{i}\times {\rm{A}}{\rm{c}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{u}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}\,{{\rm{C}}{\rm{h}}{\rm{r}}{\rm{o}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{o}}}_{i})\\ \,+\,{\gamma }_{3}{\rm{I}}{\rm{n}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{t}}{\rm{i}}{\rm{a}}{\rm{l}}\,{{\rm{A}}{\rm{l}}{\rm{g}}{\rm{o}}}_{i}+{{\bf{X}}}_{{i}}^{{\prime} }{\boldsymbol{\Gamma }}+{\varepsilon }_{i}\end{array}$$

(2)

Hat() denotes the fitted value from the corresponding first-stage regression. The two first-stage regressions predict the following:

Hat(Initial Chronoi × Actual Algoi) with Initial Chronoi × Treatment Algoi and Hat(Initial Algoi × Actual Chronoi) with Initial Algoi × Treatment Chronoi. With a compliance rate of 85.38%, the instruments are extremely strong: in all specifications, the F-statistics for the excluded instruments in the first stage exceed 1,000.

In equation (2), γ1 represents the LATE estimate of the effect of switching the algorithm on, and γ2 the corresponding effect of switching it off. The main LATE estimates are reported in Extended Data Fig. 3. Given the high compliance rate, the ITT and LATE estimates are very similar.

In Supplementary Information Fig. 2.13, we also report LATE estimates using a more conservative definition of self-reported compliance, in which a respondent is considered compliant only if they answered ‘always’ to the question ‘Did you stick to the assigned feed?’ For those who answered ‘almost always’, we assume that they complied with the assigned setting at any moment only with probability 0.5. In this case, the instruments remain very strong and the results are very similar.

The results are also robust to restricting the analysis to respondents whose compliance was confirmed through observation, that is, those who installed the Google Chrome extension and remained on their assigned feed setting (Supplementary Fig. 2.12).

Attrition and Lee bounds estimates

Significant attrition was observed between the pre-treatment and post-treatment surveys, common to studies like ours. Attrition rates did not differ across treatment groups. We formally assess whether selective attrition could bias our results using Lee bounds and conclude that attrition does not meaningfully affect our findings. Details are provided in Supplementary Information section 1.8.2, and results are reported in Extended Data Fig. 6.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval for this research was granted by the Ethics Committee of the University of St. Gallen, Switzerland. All procedures involving human participants were performed in accordance with the institutional guidelines and regulations. Informed consent was obtained from all participants at the time of their enrolment. Participants received compensation for their time: they were compensated in points—a currency used within our implementation partner’s (YouGov) platform, with an exchange rate of 1,000 points equalling US$1.00. For the pre-treatment survey, they received 500 points (US$0.50), with clear information that they would earn 2,500 points (US$2.50) for using the assigned feed setting between the two surveys and returning for the post-treatment survey. Furthermore, participants could earn an extra 2,000 points (US$2.00) for using the Chrome extension during the pre-treatment survey. After completing the post-treatment survey, they were paid the 2,500 points (US$2.50) that had been announced during the pre-treatment survey. Again, they could earn additional compensation for running the Chrome extension, this time 2,500 points (US$2.50). Therefore, participants could earn up to 10,000 points (US$10.00) if they completed both surveys and used the Chrome extension both pre- and post-treatment. Sharing the X handle was not incentivized.

The experimental interventions were limited to the choice of feed setting, which is freely available to every user on the X platform. No artificial manipulation of users’ content was introduced. Additional information on ethical safeguards and considerations is provided in Supplementary Information section 1.1.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this