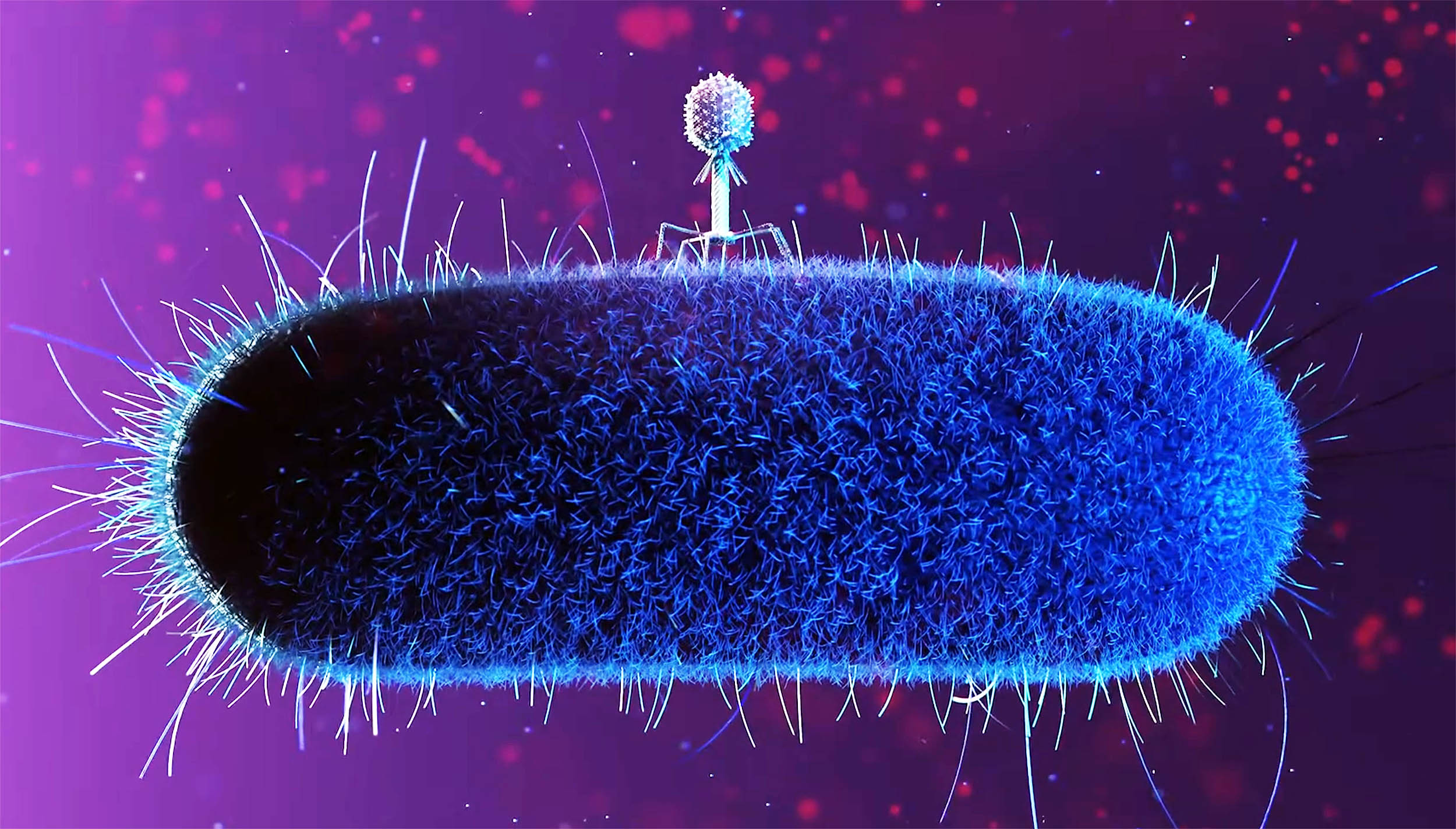

Viruses that infect bacteria can still do their job in near-weightlessness on the International Space Station (ISS).

However, the pace of infection shifts, and both the virus and the bacterium start evolving along different paths than they do on Earth.

A team led by Phil Huss at the University of Wisconsin–Madison tracked what happened when the bacteriophage T7 (a classic virus used in labs) met its usual host, E. coli, in microgravity.

The experts compared matched samples incubated in orbit versus on Earth, then looked at how infection unfolded and what genetic changes piled up over time.

Mutated phages in space

On Earth, a phage “wins” by bumping into the right bacterium, sticking to it, injecting its genetic material, and forcing the cell to manufacture new virus particles.

The timing of that encounter depends on physics as much as biology. Mixing, convection currents, sedimentation, and the constant reshuffling of nutrients and waste products all increase the chances that viruses and bacteria collide.

In microgravity, that background motion changes. With buoyancy-driven convection largely gone, fluids don’t circulate the same way.

Microbes experience a very different environment for transport, diffusion, and local build-up of byproducts.

At the same time, bacteria can shift their physiology under spaceflight conditions – including the kinds of outer-membrane molecules that phages use as “handles” to attach.

So the big question isn’t just “can infection happen?” It’s whether the whole coevolutionary tug-of-war between bacteria and phage plays out differently when the physical world is weird.

A simple test on the ISS

To isolate the effect of microgravity as cleanly as possible, the researchers prepared two identical sets of sealed samples in cryovial tubes. One set went to the ISS; the other stayed on Earth as a control.

The team used a non-motile E. coli strain (BL21) to remove swimming-driven mixing from the equation, and they incubated everything at 37°C without shaking.

The experts then checked what happened at short time points (1, 2, and 4 hours) and at a long time point (23 days).

The short windows were meant to catch the early infection dynamics. The long window gave both organisms time to propagate and adapt, if they could.

Space phages act differently

Under typical lab conditions, T7 can infect and burst open E. coli quickly. In this experiment, even the Earth-based samples showed a noticeable slowdown, with infection effectively happening between 2 and 4 hours.

In microgravity, the slowdown was much stronger. The phage didn’t show the same clear signs of replication during the first few hours.

But the key point is that it wasn’t a dead end. By the 23-day mark, the space-grown phage had clearly managed to replicate and persist, meaning productive infection still happened – only on a dramatically stretched timeline.

That “late start” matters because timing is part of survival. A delay changes how many bacterial cells are available, how stressed they are, and what kinds of defenses they can mount before the virus really gets rolling.

Different evolutionary solutions

Once the team confirmed the long-run infection outcome, they looked at genetics.

Whole-genome sequencing showed that both sides – virus and bacterium – accumulated new mutations, but the patterns differed between space and Earth.

On the phage side, mutations were spread across the genome, including in proteins tied to infectivity and host interaction.

In microgravity, certain phage genes stood out for enrichment of changes, suggesting that the virus was being pushed toward a different set of “best moves” than it would normally use on Earth.

Bacteria under pressure

On the bacterial side, mutations were especially common in genes linked to the outer membrane and stress responses.

These are exactly the kinds of systems that could both help a bacterium cope with microgravity and make it harder for a phage to latch on.

The sequencing also suggested that phage pressure itself was a big driver. Bacteria exposed to phages accumulated more notable mutations than bacteria incubated without phages.

In other words, the “arms race” didn’t stop in space. It just took a different route.

The key that unlocks infection

The team then zoomed in on one critical tool: the T7 receptor-binding protein, the part of the phage that recognizes the bacterial surface and helps initiate irreversible attachment.

They used deep mutational scanning – essentially generating a large library of single amino-acid variants in a key region of that protein – to map which changes helped or hurt the phage under each condition.

The result wasn’t a small tweak. The “fitness landscape” of mutations looked meaningfully different in microgravity compared with Earth.

The results indicate that the host environment had shifted enough to change what the phage was being rewarded for, mutation by mutation.

Space phages on Earth

Here’s the twist that makes the story bigger than space biology. The researchers used microgravity-enriched insights to assemble combinatorial phage variants.

The variants were tested against two clinically isolated uropathogenic E. coli strains (UTI1 and UTI2) associated with urinary tract infections.

These are strains that are resistant to wild-type T7 under normal terrestrial conditions. The microgravity-informed variants showed improved activity, while a comparable “Earth-informed” library did not show the same boost.

That doesn’t mean space is a magic phage factory. But it does suggest microgravity can expose evolutionary routes – and useful molecular tweaks – that are harder to stumble upon in standard lab conditions.

Discoveries in extreme environments

For long-duration spaceflight, the immediate lesson is practical. Microbial ecosystems in orbit may behave in ways that are familiar in outline (infection still happens) but unfamiliar in detail (timing, selection pressures, and adaptation routes).

For medicine on Earth, the lesson is more opportunistic. Extreme environments can act like discovery engines, revealing new design principles for engineering phages that perform better against hard-to-treat bacteria.

“Space fundamentally changes how phages and bacteria interact: infection is slowed, and both organisms evolve along a different trajectory than they do on Earth,” noted the researchers.

“By studying those space-driven adaptations, we identified new biological insights that allowed us to engineer phages with far superior activity against drug-resistant pathogens back on Earth.”

The study is published in the journal PLOS Biology.

—–

Like what you read? Subscribe to our newsletter for engaging articles, exclusive content, and the latest updates.

Check us out on EarthSnap, a free app brought to you by Eric Ralls and Earth.com.

—–

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this