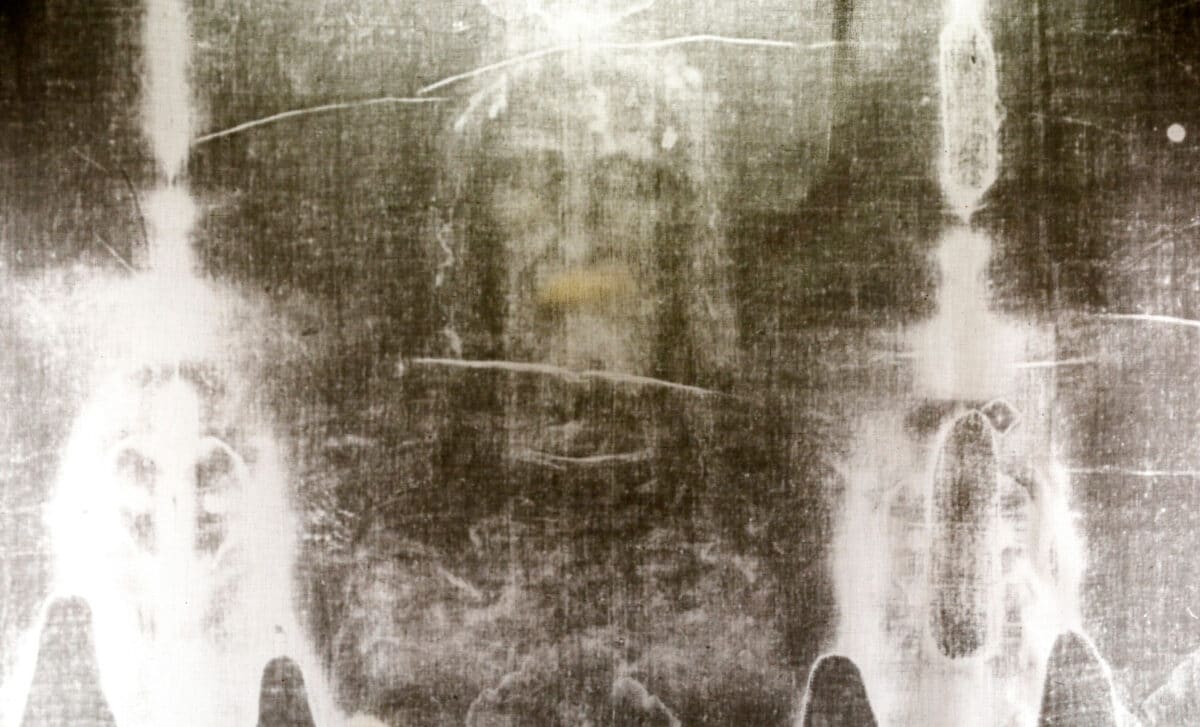

First recorded in the 14th century, the Shroud of Turin has captivated believers and skeptics for generations. The linen cloth appears to show the face and body of an adult man with long hair and a beard, closely matching the way Jesus Christ has traditionally been depicted since around the 6th century A.D. Though faint to the naked eye, the image becomes strikingly clear when viewed as a photographic negative.

For centuries, many have believed the cloth to be the burial shroud placed around Jesus after his crucifixion, marked by his divine nature. Others, including prominent religious figures, have pushed back. Now, a new study using open-source software revisits an older theory with modern tools, and reaches a pointed conclusion.

A Relic Questioned Since the Reformation

Skepticism about the Shroud is hardly new. One of its most famous critics was John Calvin, the 16th-century French theologian and namesake of Calvinism. In his Treatise on Relics, Calvin directly challenged claims that the cloth bore a miraculous image.

“How is it possible that those sacred historians, who carefully related all the miracles that took place at Christ’s death, should have omitted to mention one so remarkable as the likeness of the body of our Lord remaining on its wrapping sheet?” he wrote.

Calvin pointed out that none of the disciples mentioned seeing such an impression. He also noted that Roman soldiers were unlikely to have allowed Christ’s followers to take possession of such an item. Citing the Gospel of John, he argued that Jesus was buried “according to the manner of the Jews,” which would have involved separate cloths for the body and the head, not a single sheet. “In short,” Calvin concluded, either St. John was lying, or those claiming to possess the holy sudary were guilty of falsehood and deceit.

Despite these objections, the mystery endured, largely centered on one question: if the image is real, how did it get there?

Testing a Decades-Old Theory with Modern Software

The new investigation was led by Cicero Moraes, a Brazilian researcher and 3D designer. According to Popular Mechanics, Moraes used the free programs MakeHuman and Blender to test a hypothesis first proposed in the 1980s by Walter McCrone, who described the Shroud’s image as “an inspired painting.”

At the core of the theory is a simple geometric problem. If a cloth had been wrapped around a fully three-dimensional human body, the resulting image, once the fabric was laid flat, would appear distorted and flattened.

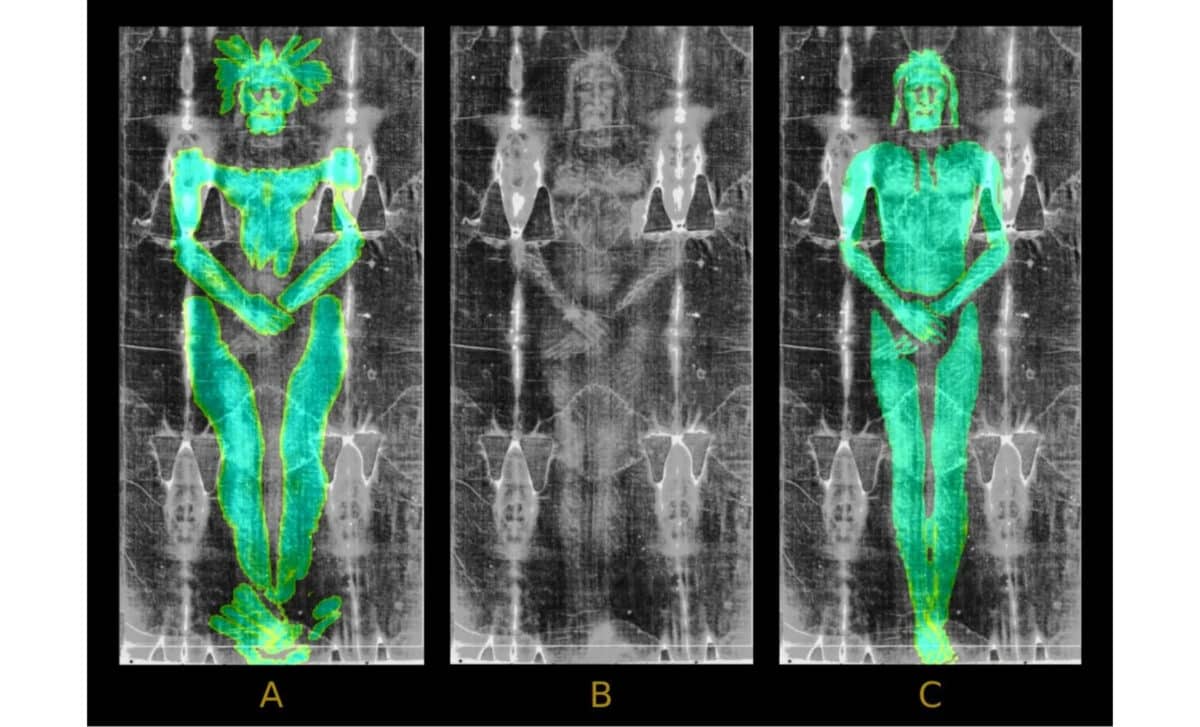

To explore this, Moraes created a digital model defined as male, adult, approximately 33 years old, thin, and about 1.80 meters tall. He refined the model in Blender to better match the proportions seen on the Shroud. He then simulated two scenarios: fabric wrapped around a three-dimensional body, and fabric placed over a low-relief sculpture.

What Fabric Reveals When It Meets Form

The simulations produced a clear contrast. According to the findings published in Archaeometry, when a three-dimensional object leaves marks on fabric, the stains generate a “more robust and more deformed structure in relation to the source.” In other words, the image becomes visibly warped when flattened.

A simple comparison illustrates the point. If a globe were coated in ink and wrapped in cloth, unfolding that cloth would not reveal a clean circular projection. The curvature would stretch and distort the imprint. Moraes also demonstrated the principle in a video accompanying his study notes, showing how anyone could replicate the effect by applying pigment to a face and pressing fabric or paper against it.

By contrast, when fabric was placed over a low-relief form rather than a fully rounded figure, the resulting image showed far less distortion. Moraes’ work concludes that the Shroud’s image aligns more closely with a low-relief artistic method than with a direct imprint from a human body.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this