We are living in the age of maximum AI hype: A superintelligence that surpasses humanity is going to emerge at any moment, according to the most breathless corners of the tech world.

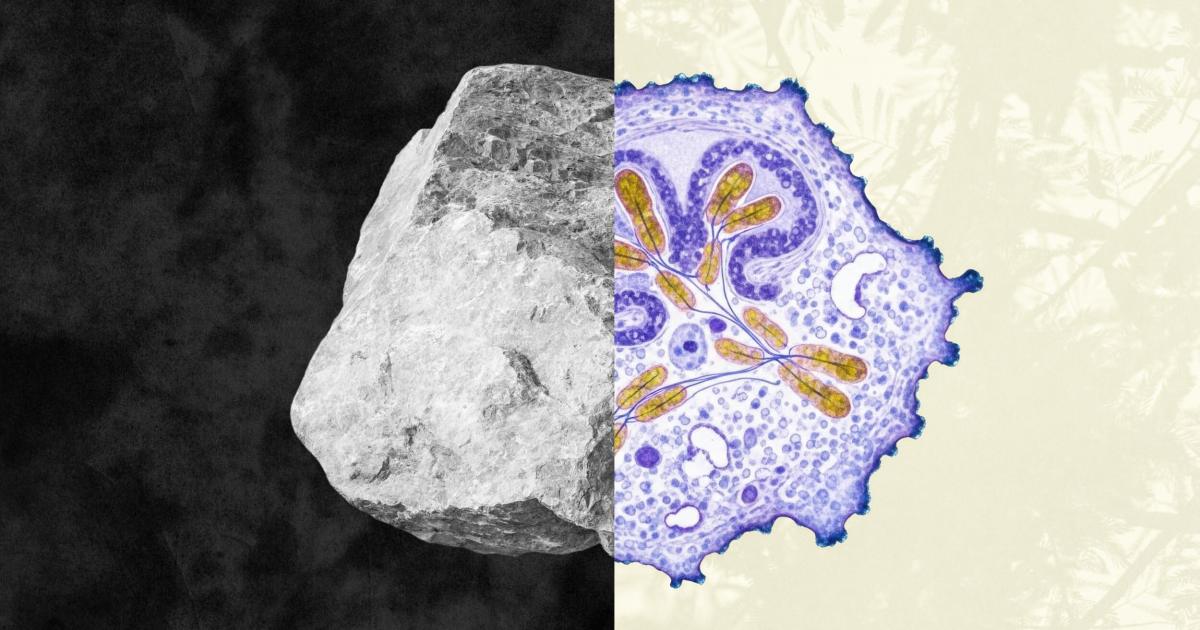

There are basic technical grounds to be skeptical of that claim, but beyond that, a much deeper issue lies at the boundary between science and philosophy: What makes life different from non-life? Why is a rock inert and insensate, while even the simplest cell manifests open-ended activity in the relentless pursuit of staying alive? Since the only systems that indisputably display intelligence are alive, if we can’t understand life, we’re probably missing something essential about intelligence.

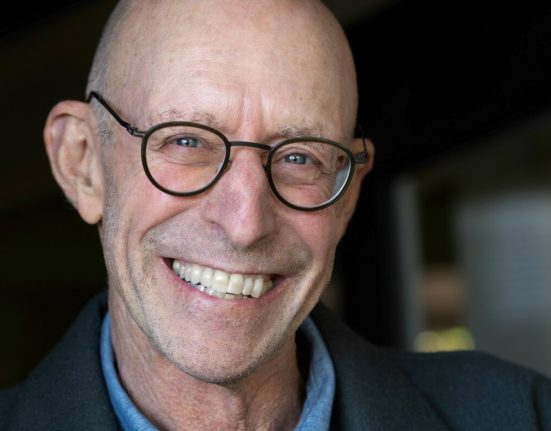

Sixty years ago, an influential but little-known philosopher named Hans Jonas gave a potent, creative, and radical answer to this question of what makes life different from non-life. In the decades since, the power and reach of his perspective have gained traction. Today, for a growing group of researchers — in fields ranging from neuroscience to the physics of complex systems — Jonas has become an incisive voice arguing forcefully that organisms are more than just machines, and minds are more than just computers.

A philosophy of life

Jonas was born in Germany in 1903. For his PhD, he studied phenomenology, a then-new approach to philosophy that attempts to study conscious experience from the inside. His PhD advisor was Martin Heidegger, one of the most famous philosophers of his time.

When the Nazis rose to power, Heidegger was initially supportive of the party. Jonas, however, fled Germany, vowing to return as part of a victorious, liberating force. He fulfilled this vow via a special brigade of Jewish soldiers fighting in the British Army. In the post-war years, as other philosophers attempted to publicly rehabilitate Heidegger (who was without doubt a brilliant philosopher), Jonas would have no part of it, instead writing a scathing repudiation of his former mentor. He never lost his interest in phenomenology or in the primacy of experience as the key to understanding life, though.

In Jonas’ time, as today, most scientists and philosophers took a “reductionist” perspective on living systems. Organisms, in this view, are simply atoms in motion. There is nothing special about life, and experience is just an epiphenomenon — an illusion or byproduct. Reductionism’s central claim is that life is nothing more than a complicated molecular machine: robots made of protoplasm, tissue, and bone programmed by evolution. Biology, like everything else, should ultimately reduce to physics.

Reductionism, however, is not a scientific result. It is not “what science says.” It’s a philosophy. It’s a set of metaphysical arguments about what exists in the world.

Jonas, as a skilled philosopher, knew there were other ways to skin that cat, and in 1966, he published The Phenomenon of Life: Towards a Philosophical Biology. In the book, he laid out a series of powerful arguments for why life is more than simply complicated physics. For a theoretical physicist like me, it’s in the book’s third chapter — “Is God a Mathematician? The Meaning of Metabolism” — that Jonas really goes for reductionism’s jugular.

Could the perfect God of perfect physics “see” life?

There is a famous story of the great physicist Pierre-Simon Laplace presenting his theory of planetary motion to Napoleon. Using Newton’s powerful mechanics, Laplace could predict the motion of the planets far into the future. Napoleon asked Laplace something like, “But where is God in your theory?” Laplace famously answered, “I had no need of that hypothesis.”

What Laplace meant was that if you knew the exact position and momentum of every particle in the Universe, then, in principle, Newton’s laws would let you predict with certainty everything that is going to happen. Of course, only a superbeing (or a godlike computer) could know the position and momenta of every particle in the Universe and compute their trajectories far into the future. That is the kind of God that Jonas is gunning for as he takes on the Laplacian dream of reducing life to “nothing but” atoms in Chapter 3 (or what’s called “The Third Essay”) of his book.

Imagine, Jonas says, that such a God is going about its business of following particles as they careen off one another like an infinite spray of micro-marbles extending through infinite space. This God would watch as collections of atoms came together to form associations for some time before dissolving again as their motions carried them away. Some of those associations might be rocks. Some might be stars. And some might be living organisms.

From there, Jonas asks a simple question: Could this Laplacian God recognize the living associations from the dead ones? Could this perfect God of perfect physics “see” life?

To frame the question, Jonas notes that life is not simply the matter from which it’s composed. Instead, every organism is what physicists call an “open thermodynamic system.” The atoms you’re made of today are not the atoms you will be made of a year from now. Energy and matter are constantly flowing through every cell. This means that living systems are not stable collections of atoms like a rock. Instead, they are stable patterns that persist through time.

Another way to say this is that life is not about specific bits of matter — it’s about a specific kind of organization through which matter and energy pass. This emphasis on “organization” becomes a central point in Jonas’ argument. The Laplacian God can only see states of atoms — their positions and velocities — at each moment. Its ability to see the future is limited to just seeing future atomic states (i.e., future positions and velocities). For Jonas, no momentary state of a body could contain the secret of being alive, no matter how detailed that state was described.

Jonas is asking if the Laplacian God, knowing only the momentary clouds of atomic associations, could tell the difference between a living body with its experience and a newly deceased corpse that had none.

What makes an organism?

The cutting power of this insight becomes sharper when Jonas begins unpacking the unique kind of organization organisms embody.

It was the great philosopher Immanuel Kant who first articulated the idea that living systems are self-organized. The classic example of this is the cell membrane, which is necessary for the cell to function but is also a product of the cell’s function. This chicken and egg self-referentiality is what Jonas means in highlighting the word “metabolism” in the chapter title. For him, metabolism is not simply a sequence of biochemical reactions. It’s the ongoing self-referential self-organization that must continue if an organism is to maintain itself (i.e., stay alive). For him, differences between life and death do not revolve around particular material components. Instead, they lie in the ongoing performance of a certain kind of activity: the self-organization of metabolism.

For Jonas, metabolism represents a profound new dimension of possibility that emerges into the Universe when life forms — one to which the Laplacian God would be blind. Thus, even as this God would know everything about atoms and their motions, it could not know what was happening in the living systems. As Jonas famously wrote, “Life can be known only by life.”

Life always has purpose.

What specifically emerges in this new dimension made possible by metabolism? Jonas articulates a series of “features” that make life unique compared to other objects or systems in the Universe.

The first and most important features are interiority and individuality. Even the simplest cells exist as individuals that live within a boundary separating interior (self) from environment (world). It’s here that you can see Jonas’ interest in experience as a philosophical question. For him, all life, even the simplest bacteria, have a degree of sentience: the feeling of being alive. The cell’s individuality is a process that it must actively maintain for itself through its own actions — actions that are only possible because it actively maintains its self-organization. In a sense, the self-referential loop of those actions is experience. How could the Laplacian God see the interiority and the experience that emerged with the cell?

An essence of what distinguishes life is what Jonas calls “needful freedom.” Every organism must actively maintain itself against the continuous threat of its own dissolution. The boundary that defines interiority and individuality is the freedom that came into being when life formed. By becoming an individual, the life-form is free or separate from the environment in a way that’s impossible for a rock. Jonas’ co-emphasis on need, however, is the organism’s endless and ongoing dependence on the world for the materials required for metabolism. Because of this need, life is inherently precarious.

This knife’s edge on which all organisms balance — from bacteria to humans — introduces another dimension into being: purposiveness. Life always has purpose. For bacteria, the purpose is simply to stay alive. As organisms become more complex, new purposes emerge, such as maintaining status within social networks or, eventually, creating meaning through activities like art or science. Purpose is intrinsic to organisms. With the emergence of life, something “for the sake of which” has been introduced into the Universe that, again, the Laplacian God could neither see nor predict.

A new perspective on life

In building his arguments, Jonas was rejecting both dualism, which sees mind and matter as entirely different, and reductionism, which rejects life as having a special status above mere mechanics. For Jonas, there was a world of matter from which life emerged — but what emerged was fundamentally new and different from what came before. While scientists and philosophers continue to debate the nature of such emergentism, there is no doubt that Jonas’ work triggered a slow, steady reconsideration of life beyond reductionism.

A clear example of this is the idea of autopoiesis, a term coined by the great Chilean biological theorists Umberto Maturana and Francisco Varela in the late 1970s. A system is autopoietic when it is both self-creating and self-maintaining. Maturana and Varela’s further work on autopoiesis in the 1980s and ‘90s was an explicit scientific attempt to articulate the special nature of biological self-organization.

Another step in Jonas’ direction came with theoretical biologist Robert Rosen, who, also in the 1980s, developed a mathematical account of organisms as “metabolism-repair systems,” or “(M,R) systems.” Rosen articulated the key theoretical concept that metabolism, in Jonas’ sense, was causally closed. This meant metabolic systems could be viewed as a special kind of organization where networks of processes close back on themselves. Break any of the links in the network, and the organization — the self-organization — falls apart. From this, Rosen claimed it was possible to show that such (M,R) systems were not Turing computable, meaning their behaviors could never be fully captured in a computer simulation.

While their work was initially not accepted in the scientific mainstream, Maturana, Varela, and Rosen were scientific pioneers. Over the past few decades, terms like “autopoiesis” have begun appearing more frequently in the study of complex adaptive systems, a modern, multidisciplinary approach to understanding life.

While reductionist perspectives still tend to dominate in science, there is a growing understanding that its value has played out, and that new approaches are needed to tackle cutting-edge problems in life, cognition, and intelligence, wherever they may be found. This is particularly true in light of the rapid advances in AI. Claims about the immanence of superintelligence or sentient AI agents run headlong into Jonas’ penetrating analysis about what makes life — as the only systems which show agency, sentience, and intelligence — different.

As the new non-reductionist approaches gain traction and bear fruit, they will have a direct effect not only on these AI debates but also on science as a whole. Through it all, it will be Hans Jonas, the principled philosopher of life and experience, who will stand as a true pioneer of the new vision of life and nature. In his quiet way, he took the first brave steps toward making us aware of the needfully free, radically new dimension of the cosmos each of us represents.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this