Strains and media

Strains used are listed in Supplementary Table 2 and plasmids in Supplementary Table 3. Strains and plasmids are available on request. Hanseniaspora strains were grown in standard rich medium (YPD; yeast extract, peptone, dextrose) or in synthetic complete dropout medium at 30 °C.

DNA extraction and Nanopore sequencing

DNA for nanopore sequencing was prepared as previously described in ref. 66. In brief, overnight cultures of Hanseniaspora spp. (roughly 5 ml of YPD) were pelleted by centrifugation, washed with 1× PBS and resuspended in 5 ml of spheroplast buffer (1 M sorbitol, 50 mM potassium phosphate, 5 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) supplemented with 5 mM dithiothreitol and 50 mg ml−1 zymolyase. Cultures were incubated at 30 °C with shaking at 210 rpm for 1 h. The resulting spheroplasts were collected by centrifugation at 2,500g (4 °C), gently washed with 1 M sorbitol and treated with a proteinase K solution (final concentration 25 mM EDTA, 0.5% SDS, 0.5 mg ml−1 proteinase K) for 2 h at 65 °C, with gentle inversion every 30 min. Genomic DNA was extracted twice using a 1:1:1 ratio of phenol:chloroform:isoamyl alcohol. The aqueous layer was treated with roughly 10 µg of RNase A at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by a final 1:1 extraction with chloroform:isoamyl alcohol. DNA precipitation was carried out using 0.1 volume of 3 M sodium acetate (pH 5.2) and 2.5 volumes of ice-cold 100% ethanol, with inversion until visible DNA strands formed. High-molecular-weight DNA was spooled onto a pipette tip, washed in 70% ethanol, air-dried and dissolved overnight in Tris-EDTA buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA). DNA quantification was performed using the Qubit 1× dsDNA HS Assay reagent (Thermo, Q33231) on the Qubit Flex Fluorometer. For sequencing, genomic DNA was simultaneously tagmented and barcoded with the Oxford Nanopore Rapid Barcoding Kit (SQK-RBK004) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Barcoded libraries were pooled, purified and concentrated using Sera-Mag beads (Cytiva, 29343052). The prepared library was immediately loaded onto a MinION R9.4.1 flow cell (SKU, FLO-MIN106.001) and sequenced on a GridION Mk1 device for 46 h.

Hi-C library generation

Cultures (YPD) were inoculated with the desired strain and grown overnight at 30 °C. The following morning, each was diluted into 150 ml of YPD at a starting optical density (OD) with absorbance at 600 nm (A600) of 0.25 and each was grown until an OD of A600 = 0.8–1.0. Cells were crosslinked in formaldehyde [3% (v/v)] for 20 min at room temperature and the reaction was quenched with glycine (300 mM). Cells were then collected by centrifugation and washed twice in fresh YPD. Last, the cell pellet was frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80 °C until further processing. Hi-C experiments and library generation were then performed as previously described in refs. 67,68,69.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Raw fastq reads were first processed with porechop (v.0.2.4) to remove barcodes and adaptor sequences. We then generated de novo genome assemblies using Canu (v.2.2; genomeSize = 10 maxInputCoverage = 100). Contigs were polished in the following manner: first, raw contigs were corrected using the ultrafast consensus module Racon (v.1.4.17), followed by two sequential rounds of contig polishing with Medaka (v.1.7). Finally, we performed three rounds of contig polishing with Pilon (v.1.23) using publicly available Illumina sequencing datasets from each species (Sequence Read Archive (SRA) accession numbers SRX5619117, SRX5619118 and SRX5619119). Next, the polished contigs were scaffolded using chromatin conformation sequencing data (Hi-C) with the 3D-DNA pipeline (v.180922)70. Scaffolded assemblies were manually corrected using the Hi-C map visualization and editor Juicebox (https://github.com/aidenlab/Juicebox). The final assembly statistics are reported in Supplementary Table 1.

We generated a reference-assisted assembly of the Sa. ludwigii strain PC99/R1 using publicly available shotgun sequencing data (SRA SRR12082187). First, we generated a de novo genome assembly using the SPAdes (v.4.1.0) assembler. This resulted in an assembly of 408 contigs larger than 500 bp, with a contig N50 of 87,147 bp. We scaffolded the contigs using ragtag (v.2.1.0) with the assembly UHD_SCDLUD_16 (strain NBRC 1722) as the reference. The PC99/R1 assembly was used to extract extra centromere regions as they were divergent from strain NBRC 1722. In total, the assembly of PC99/R1 contained five out of seven centromeric regions.

We generated de novo genome assemblies of three strains of Sa. pseudoludwigii using the Plasmidsaurus hybrid yeast genome service. Cells were grown in YPD at 30 °C until saturation, collected by centrifugation, washed with 1× PBS and 75 mg of wet cells were resuspended in 500 µl of Zymo 1× DNA/RNA Shield (catalogue no. R1100-50). The preserved specimens were then shipped to Plasmidsaurus. Genome sequencing and assembly were completed using Oxford Nanopore Technologies and Illumina sequencing with Plasmidsaurus’s custom analysis and annotation pipeline.

Genome annotations

Genomes of the three Hanseniaspora species were annotated following the previously published methods of the Y1000+ consortium26. Genome completeness was then assessed with BUSCO, which yielded expected results for Hanseniaspora species71 (Supplementary Table 1).

Hi-C data analysis

The HiCLib algorithm was used to generate contact maps from paired-end reads72. Read-pairs were mapped independently using Bowtie2 (v.2.2.9: –very-sensitive, –rdg 500, 3; –rfg 500, 3)73 on the corresponding MboI-indexed reference sequence. Unwanted restriction fragments were filtered out (for example, loops, non-digested fragments, as described in ref. 74) and valid restriction fragments were binned into 5-kb bins. Contact maps were finally filtered and normalized as previously described in ref. 75.

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

Chromosomes from stationary yeast cultures were prepared in agar plugs using Certified Megabase Agarose (Bio-Rad, 1613108). Roughly 10 mg of wet cell pellet was used for preparation. Each cell pellet was then rapidly resuspended with the zymolyase solution (25 mg ml−1 20T zymolyase in 10 mM potassium phosphate, pH 7.5) and low-melting-point agarose cooled to 42 °C (0.5% in 100 mM EDTA, pH 7.5). This mixture was quickly mixed by pipetting and transferred to the agar plug moulds. After setting (30 min), plugs were transferred to a 50-ml Falcon tube containing 1 ml of 500 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris (pH 7.5) and incubated at 37 °C overnight. The following morning, 400 µl of proteinase K solution (5 mg ml−1 proteinase K, 5% sarcosyl, 500 mM EDTA, pH 7.5) was added and samples were incubated for 5 h at 50 °C. Last, plugs were washed once in water, and then three times in Tris-EDTA buffer. Plugs were stored at 4 °C in Tris-EDTA buffer until use. Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis was then carried out using the running conditions for Hansenula wingei (Wickerhamomyces canadensis; Bio-Rad Catalogue 170–3667). Chromosomes from S. cerevisiae (0.225–2.2 Mb, Bio-Rad; 1703605) and W. canadensis (1.05–3.13 Mb, Bio-Rad; 170–3667) were used as molecular weight standards. Chromosomes were then separated on a 0.8% agarose gel in 1× TAE buffer (Certified Megabase Agarose Bio-Rad, 1613108) following the program details for Hansenula wingei chromosomes, on a Bio-Rad CHEF-Mapper XA system.

Hanseniaspora uvarum genetic transformations

Hanseniaspora uvarum strain HHO44 was transformed by electroporation following a previously published method in refs. 76,77. mNeonGreen was first subcloned into a DNA fragment encoding H. uvarum Cse4 (strain HHO44) with mNeonGreen inserted at residue valine 60, a region previously targeted for internal integration of green fluorescent protein in S. cerevisiae17. The fragment was then cloned into a vector containing a hygromycin resistance cassette (hphMX, with the promoter and terminator of H. uvarum TEF1), flanked by homology arms targeting the native Cse4 locus (730 bp upstream and 997 bp downstream). Next 1 µg of linearized plasmid was used per transformation. Transformants were grown on YPD supplemented with 400 µg of hygromycin B for selection of hphMX.

To visualize the mitotic spindle in live H. uvarum cells, we constructed a fluorescently tagged α-tubulin allele (TUB3–mScarlet). A modified H. uvarum TUB3 gene was cloned into pUC18, incorporating an N-terminal mScarlet fluorescent tag followed by a LEU2 selection cassette inserted immediately downstream of the TUB3 stop codon. The construct also included 1,158 bp of upstream and 1,026 bp of downstream genomic sequence to provide homology arms for targeted integration at the TUB3 locus. The resulting plasmid was linearized with XhoI and electroporated into H. uvarum Cse4–mNeonGreen cells. Transformants were selected on synthetic complete medium lacking leucine (SC-Leu), and integration at the TUB3 locus was verified by fluorescence microscopy.

For episomal centromere vectors, we cloned each pericentromeric region identified by Hi-C into the vector pJJ3252 (H. uvarum ARS/Leu2 vector). Details on critical DNA constructs are shown in Supplementary Note 7.

We carried out several plasmid growth assays to assess the toxicity of centromeric plasmids. These fall into three categories. (1) Growth after transformation: a measure of growth rate immediately following plasmid introduction (Extended Data Fig. 2g,k). Transformation plates were incubated for 2 days at 30 °C and imaged; under these conditions ARS (short DNA sequence)-only transformants form fully grown colonies, whereas CEN–ARS transformants show delayed growth. (2) Growth in selective conditions: a measure of the direct effect of plasmids on growth under selection (Extended Data Figs. 2l and 3b). Here cells were grown overnight in selective medium and then immediately spotted onto selective plates, incubated for 2 days at 30 °C and imaged. (3) Growth after non-selective outgrowth, which reports both toxic growth effects and plasmid loss (Extended Data Fig. 2h–j). In these assays, cells were first grown in selective medium, then once in non-selective medium to allow plasmid loss and subsequently spotted onto selective plates, incubated for 1 day or 2 days at 30 °C and imaged.

We also performed two types of plasmid retention assay. First, we measured the fraction of plasmid-bearing cells in a population under selection (Extended Data Fig. 3a). Plasmid transformants were grown in selective medium to mid-log phase and plated in parallel onto selective and non-selective plates; the ratio of colonies on selective versus non-selective plates gives the fraction of cells that carried the plasmid during mid-log growth. Second, we performed a classical retention assay (Supplementary Table 5). Plasmid transformants were grown in selective medium, then once in non-selective medium to saturation and plated onto non-selective plates. After colony formation, colonies were replica-plated to selective medium to identify those retaining the plasmid; the ratio of colonies growing on the replica-plated selective plates to the original non-selective plates provides a measure of plasmid retention.

Crosslinked MNase ChIP–seq and MNase-seq

Cultures (YPD) were inoculated with the desired strain and grown overnight at 30 °C. The following morning, each was diluted into 150 ml of YPD at a starting OD of A600 = 0.25 and each was grown until an OD of A600 = 0.8–1.0. Cells were crosslinked in formaldehyde [1% (v/v)] for 10 min at room temperature and the reaction was quenched with glycine and incubated for 5 min (125 mM). Crosslinked cells were then washed twice in ice-cold PBS and frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C.

Pellets were thawed and spheroplasts generated as previously described in ref. 66. Spheroplasts were then resuspended and washed in MNase digestion buffer (1 M sorbitol, 50 mM NaCl, 10 mM TRIS-HCl (pH 7.4), 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM spermidine, 0.075% NP-40, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol). Next, chromatin was digested with MNase digestion buffer supplemented with either 10 units ml−1 or 1 unit ml−1 MNase (Thermo Fisher Scientific catalogue no. EN0181) and incubated at 37 °C for 45 min. Reactions were stopped by addition of EDTA (30 mM final). For total MNase mononucleosome maps, samples were then de-crosslinked and proteins digested by adding SDS (0.5% final), proteinase K (20 mg ml−1) and incubated for 1 h at 37 °C and 2 h at 65 °C. Digested DNA was purified by phenol-chloroform extraction, and precipitated with isopropanol. DNA was then resuspended in Tris-EDTA buffer with 1 mg ml−1 RNase A and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Last, DNA was cleaned with the Zymo DNA Clean & Concentrator kit according to the manufacturer’s specifications.

For Cse4-containing nucleosomes, following MNase digestions, samples were sonicated using a Branson digital sonifier (30% power, 2.5 s on, 5 s off, 40 s total) and the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 4 °C (5 min at 16,000g). Next, the lysate was bound to ChromoTek mNeonGreen-Trap Magnetic Agarose beads at 4 °C overnight. The next day beads were washed ten times with MNase digestion buffer and DNA was directly purified by phenol-chloroform extraction. Purified DNA was used as the input for the NEB Ultra II Library Prep Kit following the manufacturer’s specifications. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NextSeq 500 with paired-end 2 × 150 bp read chemistry.

Crosslinked MNase ChIP–seq and MNase-seq data analysis

Data analysis for the MNase sequencing (MNase-seq) was carried out as before66. Demultiplexed reads were trimmed of adaptor sequences using Trimmomatic (v.0.39). Processed reads were then aligned to the H. uvarum genome (HuvaT2T, this work) using the Burrows–Wheeler aligner mem algorithm (v.0.7.7). For the mononucleosome analysis, we filtered reads with estimated insert sizes in the 120–180 bp range using SAMtools (v.1.9). Filtered reads were then used as input for mononucleosome analysis using the DANPOS (v.2) pipeline. Preprocessing and genome alignment steps for the crosslinked MNase ChIP–seq were carried out as above. We compared the counts per million from cells with tagged Cse4-mNG and cells without tagged Cse4 (wild type). The genome-wide ratio of Cse4-mNG to wild type was then visualized in the IGV browser (v.2.19.1) and TBtools (v.1.120). In addition, Cse4-mNG nucleosome dyads were determined with deepTools (v.3.5.2) using the function bamCoverage–Mnase.

Whole-genome sequencing and RNA sequencing

For whole-genome sequencing, cells were grown in triplicate to saturation (2 days at 30 °C) in SC-Leu medium. Cells were then collected by centrifugation and washed once in fresh medium and frozen at −80 °C. For RNA sequencing, cells were grown in triplicate to mid-log phase (0.6–0.8 OD600), placed on ice, collected by centrifugation at 4 °C and frozen in liquid nitrogen then stored at −80 °C. Procedures for DNA and RNA extractions were carried out as previously described in ref. 78. For whole-genome sequencing, 50 ng of purified genomic DNA was used for the input to the NEB Ultra II FS library prep kit for Illumina (NEB catalogue no. E7805L) and libraries were sequenced using paired-end 2 × 75 bp read chemistry on the NextSeq 500 platform. Analysis of ploidy levels was performed as follows. Raw reads were first processed to remove sequencing adaptors with Trimmomatic (v.0.39). Reads were then aligned to a modified HuvaT2T genome file, which has the extra episomal DNA, using the Burrows–Wheeler aligner mem algorithm (v.0.7.7). Chromosome ploidy levels and relative plasmid copy number were estimated as in ref. 78. As the strains of H. uvarum used in these experiments (HHO44 derivatives) are diploid, we normalized the chromosome copy number to an expected diploid genome of 2n = 14.

For RNA sequencing, 100 ng of purified RNA was used to prepare total RNA stranded libraries with the QIAseq Stranded Total RNA Lib Kit (Qiagen catalogue no. 180745) following the manufacturer’s specifications. Ribosomal RNA (rRNA) was depleted with the QIAseq FastSelect-rRNA Yeast Kit (Qiagen catalogue no. 334217). Libraries were then sequenced using paired-end 2 × 75 bp read chemistry on the NextSeq 500 platform. Reads were processed to remove sequencing adaptors and barcodes with Trimmomatic (v.0.39). Finally, reads were aligned to the HuvaT2T genome using the Kallisto pseudoalignment program (v.0.46.0) and data were analysed in the sleuth tool (v.0.30.0). Computed differential expression values are found in Supplementary Data 2.

Microscopy and analysis

Live-cell imaging of H. uvarum strains carrying integrated Cse4–mNeonGreen and Tub3–mScarlet constructs was performed using cells grown to mid-log phase in SC-Leu medium. Fluorescence micrographs were acquired on a 3i Marianas spinning-disc confocal microscope, and images were processed and analysed using Fiji (v.2.14).

For time-lapse imaging, we used a previously described H. uvarum strain expressing H2A–mNeonGreen, which enables tracking of cell-cycle progression76. This strain was transformed with ARS or CEN–ARS plasmids, in which the CEN–ARS plasmid carried an mScarlet reporter under the control of the H. uvarum PGK1 promoter. In each experiment, ARS-only and CEN–ARS cultures were mixed and imaged on the same coverslip so that both genotypes were recorded in parallel under identical acquisition settings. Cells were imaged at 30 °C in SC-Leu medium on a GE DeltaVision Elite widefield microscope, using the lowest illumination intensity and shortest exposure times that allowed reliable segmentation of H2A–mNeonGreen and mScarlet signals, with images acquired at 10 min intervals for up to 5 h. Images and videos were processed and quantified in Fiji (v.2.14) as previously described in ref. 76.

For single-time-point red fluorescent protein measurements, H. uvarum H2A–mNeonGreen strains transformed with ARS or CEN–ARS plasmids carrying mScarlet under the H. uvarum PGK1 promoter were grown to mid-log phase in SC-Leu at 30 °C. Cultures were imaged separately on a GE DeltaVision Elite widefield microscope in SC-Leu medium using identical illumination and exposure settings for ARS and CEN–ARS samples. For each field, background-subtracted mean mScarlet intensity was quantified per cell and normalized to the corresponding nuclear H2A–mNeonGreen intensity using Fiji, yielding a per-cell red fluorescent protein/H2A–mNeonGreen ratio used for copy-number comparisons.

Motif enrichment analysis

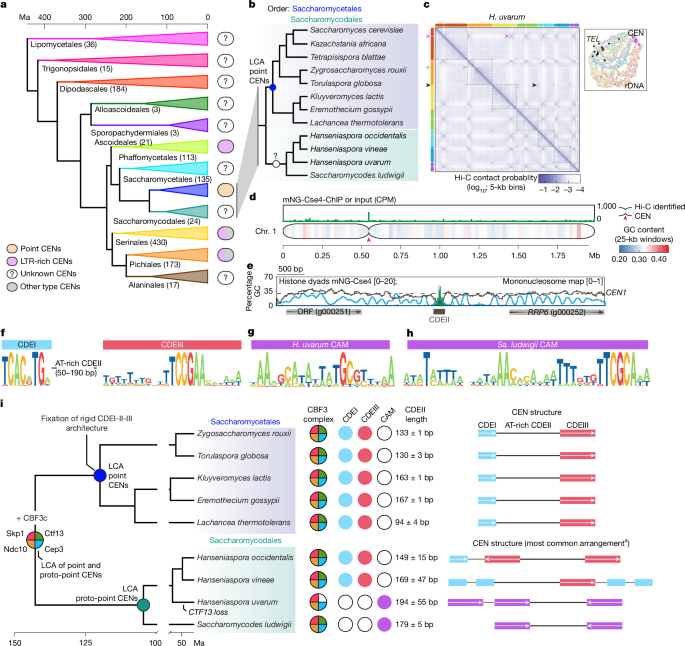

To identify DNA sequences enriched in the centromeric regions of Saccharomycodales yeasts, we used the MEME suite (v.5.5.7). First, we scanned each centromeric region for the canonical CDEI and CDEIII sequences using the FIMO function. Then, for each species’ centromeres, we performed motif discovery analysis using the MEME function (options: -mod anr, -objfun classic, -nmotifs 10 -minw 6 -maxw 50). For H. vineae, H. occidentalis and Sa. ludwigii, CDEII sequences were defined as the length of the AT-rich region between the two immediate flanking motifs.

ALG inference

As point centromeric DNAs are the fastest-evolving DNA sequences in yeast genomes79,80, we determined relatedness between proto-point and point centromeres by conserved gene synteny of pericentromeric regions. To avoid confounding effects of paralogues from the whole-genome duplication that occurred in a subset of Saccharomycetales species, we only used the genomes of species that did not experience whole-genome duplication. ALGs were inferred between Saccharomycodales and Saccharomycetales yeasts using the protein-based synteny analysis software suite, odp (v.0.3.2)81. The output of odp was manually inspected and curated to ensure accuracy in cases in which synteny blocks were erroneously fragmented due to limitations of automated synteny detection tools (Supplementary Note 3). Genome assemblies used in this analysis were downloaded from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) genome repository along with their annotations (Supplementary Data 7, dataset 1).

Divergence time of Sa. ludwigii and Sa. pseudoludwigii

To infer the divergence time of Sa. ludwigii and its sister species Sa. pseudoludwigii, we first estimated a species tree with the ROADIES pipeline (v.0.1.10)82 using six Saccharomycetales species and five Saccharomycodales species (including two strains of Sa. ludwigii and three strains of Sa. pseudoludwigii), with two outgroups (Wickerhamomyces anomalus and Cyberlindnera fabianii). The analysis converged with high internode support after four ROADIES iterations and recovered a topology consistent with the y1000+ phylogeny26. We then estimated the Sa. ludwigii–Sa. pseudoludwigii divergence using the RelTime method in MEGA v.12 (maximum relative rate ratio 45)83. Because Saccharomycotina yeasts lack a reliable fossil record, we applied a secondary calibration based on the well-estimated divergence of the S. cerevisiae–Kluyveromyces lactis split with bounds of 103–126 Myr (ref. 65). Under this calibration, RelTime divergence times within Saccharomycodales were highly congruent with state-of-the-art Bayesian estimates from subphylum-wide datasets (Pearson r = 0.995)26,65.

Ty5 LTR insertion estimates

LTR sequences are identical at the time of insertion, and the accumulation of mutations over time allows estimation of the transposable element’s age based on nucleotide divergence between the two LTRs. Sa. ludwigii LTRs were first aligned using the program MAFFT (v.7.150b)84. We then estimated the shape parameter α by maximum likelihood, using the program IQ-TREE 3 (v.3.0.1)85. This estimate of α was used to estimate the number of substitutions per site and their variance, under the maximum composite likelihood model as implemented in MEGA v.12 (ref. 83). Insertion times were then calculated using the insertion time (T) formula T = k/2 µ, where k is the estimated distance between LTRs and µ is the nucleotide substitution rate per generation (for Sa. ludwigii, 5.70 × 10−11–1.20 × 10−10 per base per generation27). Generation times were converted to time in millions of years by dividing by the number of generations per year. Under perfect laboratory conditions yeast could potentially double 2,920 times a year (8 generations a day); however, this estimate is unrealistic for wild microbial populations that experience fluctuating growth rates due to seasonal changes, nutrient availability and competition. For example, Escherichia coli doubles every 20 min in the laboratory but is estimated to double every 15 h in the wild (or a 2.22% laboratory doubling rate)86. Therefore, the annual generational rate in the wild for yeast is probably considerably lower; for example, Brewer’s yeast is estimated to double 150 times a year in the sugar-rich environments of breweries, which are continuously maintained by human activity87. Thus, we used 150 doublings as the maximum likely annual generational rate for our estimates; a more modest estimate of 2.2% of yeast’s laboratory doubling time would give an annual generational rate of 65 doublings a year. This analysis assumes LTR sequences evolve neutrally and independently, which may not necessarily be true, especially if they supply function to the centromere; thus, the estimates we provide are likely to underestimate insertion dates.

Catalogue of yeast Ty5 retrotransposons and Ty5 LTRs

Publicly available genome assemblies (accessed on 14 May 2024) were filtered on the basis of the criteria: (1) assembled to at least ‘chromosome’ level, (2) only ‘reference’ strains and (3) limited to the taxonomic group ‘Saccharomycotina’ (NCBI Taxonomy ID 147537). This resulted in a dataset of 77 species spanning 7 out of the 12 orders of Saccharomycotina yeasts (Supplementary Data 7, dataset 2). Ty5 elements were then identified using tblastx (BLAST v.2.16.0) searches with either the Saccharomyces paradoxus Ty5 element (GenBank U19263.1) or the Sa. ludwigii SaCEN-Ty5 element as the query. The significance threshold was empirically established by blasting species with known Ty5 elements and comparing e value scores for known Ty5 versus other yeast Ty retrotransposons. For example, significant matches to SaCEN-Ty5 from the species D. hansenii that corresponded to a bona fide full-length Ty5 element had an average e < 1 × 10−125, whereas non-Ty5 elements had a minimum e value no smaller than 1 × 10−68, therefore we applied a lower cut off of less than 1 × 10−68 as a putative Ty5 element. These cut offs were consistent across the species examined. Ty5 and LTR sequences were then manually annotated for each species. Centromeric regions were visualized with the ModDotPlot tool (v.0.9.4)88 or the DNA local aligner YASS (v.1.16)89.

ALG gene positioning analysis

Conserved synteny near point centromeres, proto-point centromeres and Ty5-cluster centromeres was assessed by measuring the genomic distance from each gene to the nearest centromeric region. Genomic coordinates of putative centromeres inferred by Ty5-cluster presence are provided in Supplementary Data 3. To estimate a null distribution of any random gene from its nearest centromere, we randomly sampled 100 open reading frames without replacement from the protein annotation of Zygosaccharomyces rouxii (GCF_000026365.1) using the ‘sample’ function from the Python random module (Python v.3.12). We then used tblastn to obtain genomic coordinates for each query sequence (random set of genes or the genes in CEN-ALGs). For the conserved gene synteny maps we manually annotated centromeric regions and constructed synteny maps (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Centromere sequence comparisons and phylogeny

Pairwise nucleotide divergence between centromere sequences was estimated using the Kimura 2-parameter (K2P) model applied in a sliding-window framework across the centromeric alignment (100-bp windows with 10-bp steps). Within each window, we calculated K2P distance from the relative frequencies of transitions and transversions at positions where both sequences carried canonical bases (A, C, G or T), with gapped sites excluded from distance calculations. This yielded a pairwise nucleotide divergence across the aligned centromeric region as shown in Fig. 2e.

To assess whether core centromeric sequences (CDEII elements + CAM) share compositional similarities with surrounding centromeric DNA, we performed a k-mer enrichment analysis. For each strain and centromere, the core centromeric sequences were extracted and compared against the remaining centromere sequences (LTRs and non-LTR sequences). All possible k-mers of a fixed length k (default 9 bp) were generated from each core centromeric sequence. Each k-mer was then counted in the target sequence allowing up to one mismatch. To evaluate the significance of observed matches, we constructed an empirical null distribution for each k-mer by repeatedly (10,000 permutations) dinucleotide-shuffling the target sequence, thereby preserving overall dinucleotide composition but shuffling higher-order structure. For each shuffled sequence, both orientations were considered, and the number of approximate matches of the CDEII k-mer was recorded. The observed count for each CDEII k-mer was compared with its null distribution to derive an empirical P value, calculated as the fraction of permutations in which the null count was greater than or equal to the observed count. Multiple testing correction across all CDEII k-mers within a comparison was applied using the Benjamini–Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate, and adjusted q values reported.

Centromeric alignments were done using the local DNA aligner YASS (v.1.16; seed pattern ‘very high sensitivity’, indels 20%, mutations 35%). Alignments were then filtered by their e value, with alignments considered significant if e < 0.01. LTRs and core centromere sequences were aligned using MAFFT (v.7.150b), with the options G-INS-1 and –adjustdirectionaccurately. We then inferred a maximum likelihood phylogeny using IQ-Tree (v.1.6.12) with the parameters -st DNA -m GTR + R4 + F -bb 1000 -alrt 1000. For the profile–profile alignment of LTRs, we aligned LTRs from each species using MAFFT as above. Then each species-specific alignment and core centromere alignment were aligned with each other using the profile–profile alignment feature in Seaview (v.5.05)90.

Gene presence and absence across Saccharomycotina

To map gene presence and absence across Saccharomycotina, we analysed 1,154 genomes from ref. 26 (and further Saccharomycodales genomes; Supplementary Methods). For each query gene, we identified the S. cerevisiae orthologue (or, when absent, the appropriate Schizosaccharomyces pombe or Candida albicans orthologue) and used it to seed PSI-BLAST searches against the non-redundant protein database, excluding ‘Saccharomyces’ (3 or fewer iterations, 500 or fewer sequences, e ≤ 1 × 10−3). Homologues were aligned with MAFFT (v.7.520, ‘auto’), and hidden Markov model (HMM) profiles were built with HMMER (v.3.3.2, hmmbuild). We then used hmmsearch to query all genome assemblies, retained candidates passing reciprocal BLASTP to the original query, and in most cases built a refined ‘HMMrecip’ profile from passing sequences for a second hmmsearch (final thresholds, e = 0.01 or less, bit score 50 or greater). Family-specific filters for Clr4/Set2, RNAi components and the 2µ plasmid proteins Rep1/Rep2, as well as contamination checks and genome counts, are described in the Supplementary Methods.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this