Unlock the Editor’s Digest for free

Roula Khalaf, Editor of the FT, selects her favourite stories in this weekly newsletter.

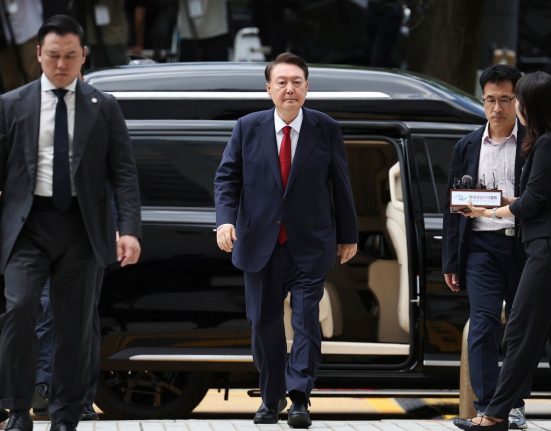

Former South Korean president Yoon Suk Yeol has been sentenced to life in prison for insurrection over his failed attempt to impose martial law that plunged the country into turmoil.

A three-judge panel at Seoul Central District Court on Thursday found that Yoon was guilty of leading an insurrection in late 2024 that attempted to subvert the constitution.

“Yoon’s acts of sedition fundamentally undermined the core values of democracy,” said judge Ji Gwi-yeon.

Yoon, 65, had faced the possibility of a death sentence.

The insurrection ruling was the second and most consequential in an ongoing series of cases against Yoon over his shock declaration of martial law. Last month, he was sentenced to five years in prison in a related case involving obstruction of justice, abuse of power and falsification of official documents.

The verdict caps a dramatic episode that plunged South Korea into its worst political crisis in decades and tested the strength of its 39-year-old democracy.

At 11pm on December 3 2024, Yoon appeared on television broadcasts in South Korea, warning that “anti-state”, pro-North Korea forces were attempting to take over the nation and declaring emergency rule to “protect the free and constitutional order”.

The order triggered widespread protests, and lawmakers climbed over barriers to the National Assembly to hold an emergency vote rejecting the martial law decree.

Facing mounting pressure, Yoon rescinded the order roughly six hours after it was issued. Ten days later, he was impeached by parliament. He was removed from office by Korea’s Constitutional Court last year.

In their ruling, the judges said Yoon had deployed troops to the National Assembly to impede lawmakers and arrest political rivals.

“The declaration of emergency martial law and subsequent military and police activities severely damaged the political neutrality of the military and police, lowered South Korea’s political standing and international credibility, and resulted in extreme political polarisation,” the judge said.

The judges attributed Yoon’s motivations to a sense of crisis brought on by the opposition-controlled assembly continually blocking legislation. But they rejected prosecutors’ claim that the emergency declaration was part of a year-long plan to establish a dictatorship.

They added that Yoon had shown no remorse for his actions.

Yoon can appeal against the verdict, and his lawyers have already criticised the verdict. South Korea’s judicial system allows criminal cases to be tried three times, including a final hearing on matters of legal interpretation by the Supreme Court.

Several other senior officials have received jail sentences in relation to the crisis. Former defence minister Kim Yong-hyun was sentenced to 30 years in prison on Thursday for his role in the insurrection.

Former prime minister Han Duck-soo, who served as acting president after Yoon’s impeachment, previously received a 23-year prison sentence for his role in facilitating the emergency measures.

An independent counsel in December exonerated Yoon’s wife Kim Keon Hee over the martial law declaration, though she received a 20-month jail sentence last month on separate corruption charges.

About 58 per cent of Koreans surveyed in January had supported a death sentence for Yoon. South Korea has not carried out an execution since 1997.

“It is difficult to view Yoon’s unconstitutional declaration of martial law as a more serious crime than former president Chun Doo-hwan’s military coup”, said Chang Young-soo, professor of constitutional law at Korea University, referring to the general who seized power in a coup in December 1979 and later ordered a massacre of civilians in the south-western city of Gwangju.

Chun was sentenced to death in 1996, but it was commuted to life in prison and he was released the following year under a presidential pardon.

Yoon’s conviction reinforces a retributive pattern in South Korean politics, where few former presidents have avoided legal peril after leaving office.

Lee Myung-bak, who served from 2008 to 2013, was imprisoned for bribery, embezzlement and abuse of power. Park Geun-hye, his successor from 2013 to 2017, faced a similar fate for abuse of power and coercion. Roh Moo-hyun, under pressure from prosecutors over allegations of bribery against his family members, took his own life in 2009.

Park and Lee also eventually received presidential pardons, the latter from Yoon.

This pattern of “extreme factional conflict” was exacerbated by a “winner takes all” system in which the president was entrusted with sweeping powers but was limited to a single term, Chang said.

Current President Lee Jae Myung’s ruling party Democratic Party has been pushing for a legal amendment to prohibit pardons and commutations for those convicted of insurrection.

Yoon had ordered Lee’s arrest as part of his martial law bid, along with leading members of the Democratic Party and his own People Power Party.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this