Animals

All experiments were conducted in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Princeton University and the guidelines and policies of the United States Department of Agriculture, as required by the Animal Welfare Act. Subjects included laboratory-bred African striped mice (R. pumilio), which originated through systematic outbreeding in a captive colony at Princeton University (obtained through Harvard University, in turn obtained through the University of Zurich) and originating from Goegap Nature Reserve, South Africa (29° 41.56′ S, 18° 1.60′ E). No wild animals were used in this study, and no samples were collected from the field. Striped mice were maintained in a temperature-controlled (22.2 °C or 72 °F) and humidity-controlled (40–55%) vivarium on a 12/12 light/dark cycle (lights ON at 07:00; lights OFF at 19:00) with water ad libidum. Standard rodent chow (LabDiet 5053, PicoLab Rodent Diet 20) was restricted to 4 g per mouse per day to prevent the onset of obesity. Sunflower seeds (roughly ten seeds per mouse) were also provided as a form of enrichment. All striped mice were housed in large polycarbonate rat cages (30.80 cm × 59.37 cm × 22.86 cm, Thoren) with a corncob and cotton-mixed bedding with a small volume of shaved aspen and sterile cotton squares for extra nesting material. Further enrichment in the home cage included a translucent red plastic tube and a plastic running wheel. Sexually naive striped mice were housed between one and five per cage. Breeding animals (including dams and sires) were pair-housed with mates and pups under the conditions described above. Sex was assigned as male or female according to visual inspection of externalized genitalia and anogenital distance at weaning on postnatal day (PND) 20 and confirmed in adulthood (at PND90 or above) with the presence or absence of testes.

Statistics and reproducibility

Statistical software

Analyses were completed in R49 (v.4.4.1) and GraphPad Prism (v.9.4.1). For all inferential statistics, a threshold of P ≤ 0.05 was used to determine significance. More methods regarding statistical analysis can be found in the Supplementary Information.

Power analysis

Power analysis for initial paternal behaviour testing used the pwr.anova.test function (R, pwr package). Initial parameters (power 0.80, Cohen’s f = 0.585) were based on published paternal behaviour studies28 and calculated to need n = 12.5. Parameters were then adjusted based on our own first cohort (n = 47: 24 SI, 23 GH, new Cohen’s f = 0.606, target power 0.80), and calculated to need n = 11.7 mice per group in a two-way comparison and 9.8 mice per group in a three-way comparison.

Reproducibility

All representative micrographs were replicated independently with similar results two or more times. This includes micrographs demonstrated in Figs. 3k,l and 4b–e,g,h and Extended Data Figs. 8c,d and 9e–g.

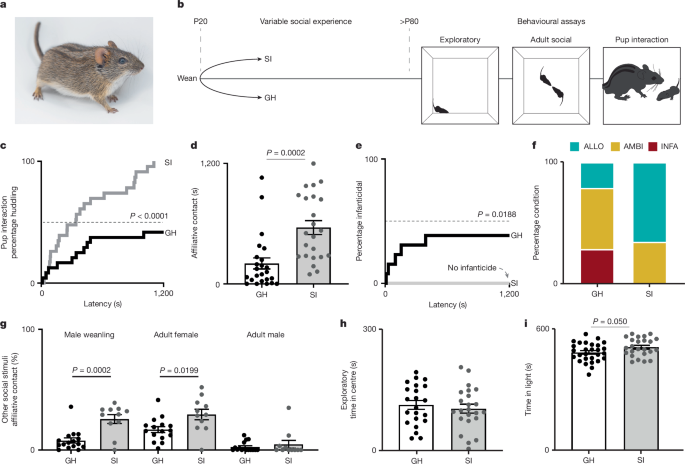

GH and SI

All mice were reared with both biological parents until weaning. At weaning, male offspring were assigned to either GH or SI conditions. GH males were weaned into new cages in groups of three to four similarly aged conspecifics (±3 days). SI males were weaned into a new cage and housed alone. All other housing conditions (for example, enrichment, feeding and so on) were equal and maintained as described above. No more than one littermate was used per condition in each experiment to experimentally control for litter effect.

Behaviour

Sexually naive male striped mice underwent social behavioural testing and exploratory and anxiety testing from PND80 or more (that is, gonadal maturity). For details on behavioural testing, other than those of the pup interaction test, refer to the Supplementary Methods.

Pup interaction test

Parental care was assayed with a 20-min pup interaction test, which was adapted from the alloparental care test used in prairie voles61. Testing occurred in a large rat cage (30.80 cm × 59.37 cm × 22.86 cm, Thoren) with a thin layer of cotton square bedding. Mice were habituated to the cage for 40 min. Following habituation, the test animal was relocated to one end of the cage and maintained within a large cup (5 s or less) while a novel pup stimulus (PND1–6) was placed in at the other extreme of the cage. Each tested male was released to interact freely with the pup. If the test animal attempted infanticide, test was immediately ended and the pup either returned to its parents (if unharmed) or euthanized by emergency decapitation. Notably, wild striped mice do not appear to distinguish unfamiliar pups from their own before PND1062. We did not control for pup sex, but we selected pups from their home nest at random. On the basis of observations, neither male nor female pup stimuli are more likely to be attacked by sexually naive males (X2 = 0.06857, P = 0.7934, from sample of 60 tests of adult, sexually naive males with 30 male and 30 female pup stimuli). Specific outcomes included durations and latency to the first presentation of key behaviours: inspection, licking or grooming, lateral contact, huddling, attack (that is, infanticide) and total caring contact (huddling + lateral contact + licking or grooming). Pup interaction tests were completed in the light cycle. Mice were fed before testing with the exception with those included in the experimental manipulation of food availability. All behaviour was digitally recorded using a top-down digital webcam (Logitech BRIO, ASIN: B01N5UOYC4). Behaviour was manually scored by a trained observer using the Behaviour Tracker software.

Initial pup interaction testing and characterization

Initial behavioural characterizations of parental care were made with a sample of sexually naive male striped mice conditioned as GH (n = 24) and SI (n = 23), as well as primiparous striped mouse fathers, that is, sires (n = 18) and mothers, that is dams (n = 7).

Categorization of behavioural phenotypes

Sexually naive males were phenotypically categorized as infanticidal, ambivalent or allopaternal. Males were categorized as infanticidal if they demonstrated pup-directed, aggressive behaviours requiring researcher intervention. Allopaternal was defined as spending 10% or more of the test duration in any caring contact and 5% or more of the test duration in huddling contact. Ambivalent males were those that were neither infanticidal nor allopaternal.

Naturalistic intervention study

Adult sexually naive GH-reared or SI-reared males were rehoused into SI (n = 20 each); a second group of GH males were maintained in GH conditions (n = 24). Half of each group were provided a standard diet of 4 g food per day per mouse, while the other half received 3 g per day per mouse. Mice were maintained in these conditions for 16 days with their weights taken every 3 days. Each mouse was tested in an open field test and a pup interaction test before and after rehousing or food restriction. Brain and blood tissue was collected from half of the mice immediately after the second pup interaction test. The remaining mice were all maintained under a standard diet (4 g per day) in their housing conditions from the previous 16 days. These mice were behaviourally tested a third time before tissue collection.

Brain-wide cFos expression mapping

For full details on tissue collection, immunohistochemistry, imaging and quantification, please refer to the Supplementary Methods. Between PND90 and PND95, 22 males (n = 11 GH, n = 11 SI) completed a second pup interaction task in which they were continuously exposed to the pup for 40 min before euthanasia. If males attempted infanticide, a new pup was placed in a tea strainer within the testing cage to allow for continued exposure. Another 20 males (n = 10 GH, n = 10 SI) were used as controls and were exposed to an empty cage. At the end of the 60-min exposure or control period, mice were anaesthetized by use of intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg kg−1) and xylazine (20 mg kg−1) and transcardially perfused with 1 ml g−1 1× PBS followed by 1 ml g−1 ice-cold 4% paraformaldehyde. Brains were extracted, postfixed, cryoprotected and stored at −80 °C until sectioning. Tissue was then sliced in sequential, 30-µm coronal slices in 120 µm intervals and directly mounted to Superfrost Plus microscope slides. Tissue was subsequently stored at −20 °C for short-term storage before immunohistochemistry. Tissue was processed with a standardize protocol for fluorescence immunohistochemistry. Primary antibodies were against cFos (1:2,000 dilution; Cell Signaling, Rabbit mAb 2250S) for all slides, and Tyrosine Hydroxylase (1:2,000 dilution; ImmunoStar, mAb Mouse 22941) for posterior sections to help in the identification of the ventral tegmental area. Secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch (Alexa Fluor 488 AffiniPure F(ab′)2 Fragment Donkey Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L), 711-546-152; and Cy 5 AffiniPure Donkey Anti-Mouse IgG (H+L), 715-175-150, both used in a 1:500 dilution). Imaging was performed with a slide scanner (Hamamatsu NanoZoomer S60, C13210-01) using a ×40 objective lens and filters or DAPI, FITC (cFos) and Cy5 (Tyrosine hydroxylase, for posterior sections) but exported at ×10 for subsequent processing using FIJI63. CFos+ density was analysed by 2 × 2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) with main effects and interactions for housing (GH versus SI) and pup exposure (exposed versus not exposed), or by one-way ANOVA with a main factor of phenotype (parental, dysparental or control). Post hoc, pairwise comparisons were only performed given significant main effects or interactions (P < 0.05). Outliers were determined at a sample level (agnostic of group or phenotype) removed region by region before ANOVAs. For correlation analysis, cFos+ density for pup-exposed mice was standardized to mean control cFos+ density for each region of interest separately. Because the distribution of the density data were not normally distributed and because our questions were related to rank order, Spearman’s rank-order correlation was calculated.

snRNA-seq

Tissue collection

MPOA of 17 striped mice were processed for snRNA-seq: Sexually naive adult males that were infanticidal (n = 3), allopaternal (n = 3) or ambivalent (n = 3), as well as dams (n = 4) and their male mates (n = 4, ‘sires’) (see Supplementary Methods for more detail).

Isolation of nuclei, library preparation and sequencing

Nuclei were isolated from frozen tissue punches in batches of four samples, counterbalanced by phenotype. The protocol for nuclei preparation was modified from 10X protocol GC000393. For more details, refer to Supplementary Methods. Isolated nuclei were transferred to the Genomics Core Facility in the Lewis-Sigler Institute for Integrative Genomics at Princeton for library preparation with the 10X Genomics Chromium system and sequencing. Libraries were prepared based on an estimated input of 20,000 and recovery of ~12,535 nuclei per sample. All subsequent sequencing was carried out on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 and samples were sequenced to a mean depth of 42,426 reads per nucleus (s.d. = 8,894) and a mean saturation of 71.64 (s.d. = 10.01).

Data analysis

For full details on how data analysis for snRNA-seq was completed, please refer to the Supplementary Methods. Data were demultiplexed by barcode and processed with 10X Genomics Cell Ranger, CellBender64 and the R package scDblFinder65 to filter and remove doublets and nuclei with high mitochondrial reads or ambient RNA and random barcode swapping. Subsequent bioinformatic steps were carried out in the R package Seurat66. Individual samples were then merged, normalized, scaled and integrated using the harmony38 package. Cells were initially separated into eight major cell classes, including astrocytes, ependymal, endothelia, microglia, myelinated oligodendrocytes, new oligodendrocytes, oligodendrocyte precursors and neurons. Neurons were separated and the neuron-specific data were reclustered and the resulting uniform manifold and approximation projection was visually examined. From there, inhibitory and excitatory neurons were explicitly split, and label transfer was performed within Seurat using hypothalamic markers associated with inhibitory and excitatory neurons from adult C57BL/6 mice, as defined in a recent comprehensive mouse hypothalamic profiling39. Inhibitory and excitatory subsets were then respectively reclustered until resultant clusters parsimoniously reflected predicted identities from ref. 39. A one-way ANOVA was run for each cluster to determine whether there were differences at the level of phenotype in cluster composition. If a significant effect was found at the level of the omnibus test, post hoc pairwise comparisons with Tukey honestly significant difference correction were made to identify the source of variance between groups. Pseudobulk analysis was carried out in all neurons more generally and on clusters predicted to be located within the MPOA to address questions about molecular processes within the broader preoptic area and more specifically within subsets of MPOA neurons as well as in active neuronal populations. Subsets were created according to IEG expression (one or more counts recorded of each respective IEG in a given nucleus). IEGs were considered separately, as the cellular processes associated with each IEG are distinct67. The primary contrast for pseudobulk analysis was that of alloparental and infanticidal sexually naive males. Pseudocounts were extracted using the AggregateExpression function in Seurat with subsequent application of the DESeq268.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization

Tissue was harvested as described above for immunohistochemistry, except mice were only perfused with 1× PBS before dissecting brains, and brains were flash-frozen in isopropanol and frozen at −80 °C in blocks of optimal cutting temperature compound. Tissue was sliced in sequential, 16-µm coronal slices and immediately mounted to Superfrost Plus microscope slides and left tissue-side up at −20 °C for 2 h to improve tissue adhesion. Slides were subsequently stored at −80 °C in small slide boxes cleaned a priori with RNase Away, with a small desiccant packet, and sealed with electrical tape until processing. Gene expression was detected by RNAscope Multiplex Fluorescent ISH V2. Probes for Agouti and eGFP were custom made and are commercially available through ACDBio (RNAscope Probe-Rpu-Asip-C3, catalogue no. 1328331-C3; EGFP-O4: catalogue no. 538851 and Rpu-Mc4r-C1: catalogue no. 1324151-C1). Probes for Agouti consisted of 11 ZZ probe pairs based on bases 2–571 of the R. pumilio coding exons for Agouti (accession JANHMN010000002 see sequence in Supplementary Methods). Probes for Mc4r (accession JANHMN010000013) consisted of 20 ZZ probe pairs from the Rhabdomys Mc4r gene. Probes for eGFP consisted of 18 ZZ probe pairs from a region spanning 1,166–1,885 bases of accession MN623123. Tissue was processed according to kit instructions with the following exceptions, excepting that tissue was treated with 10% Protease IV in lieu of 100% Protease IV. Images were initially captured and assessed using a slide scanner (Hamamatsu NanoZoomer S60, C13210-01) using a ×40 objective lens and filters or DAPI, FITC, TRTC and Cy5. Images were subsequently captured at ×40 using a Nikon A1R-STED Confocal Microscope with Simulated Emission Depletion Detector.

qPCR

MPOA tissue punches were collected identically as described above for snRNA-seq from sexually naive GH males (n = 23). RNA was extracted from tissue samples with Trizol (Invitrogen) and chloroform (Sigma) and purified using an RNeasyMicro Kit (Qiagen 74004). cDNA was created with a reverse transcription kit (HighCapRT, Applied Biosystems). All real-time semi-quantitative qPCR reactions were run in triplicate and used SYBR-green on a QuantStudio 7 (ThermoFisher). Relative gene expression for striped mouse Agouti and Agrp were quantified by qPCR and normalized to striped mouse Gapdh using the 2−ΔΔCt method. The primer sequences used for Agouti were as follows: forward: 5′-GGAGACACTTGGAGATGACAGG-3′; reverse: 5′-CTCTTCTGCTTCTCGGCTTC-3′. For Agrp: forward: 5′-TTGCTGAGTTGTGTCCTGCT-3′; reverse: 5′-GTCAGGCCTTCTGATGCCTT-3′. For Gapdh: forward: 5′-AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG-3′; reverse: 5′-TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA-3′.

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

Trunk blood was collected into protein LoBind tubes and allowed to sit undisturbed at room temperature for 30 min or more. Blood was then centrifuged at 1,500g for 10 min at 4 °C, and serum was subsequently removed and frozen at −80 °C until later use. Serum was processed by use of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay for leptin (Invitrogen KMC2281) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Results were read on a Tecan Spark plate reader at 450 nm (outcome), 540 nm (background) and 570 nm (background). Before analysis, results of the 540-nm reads were subtracted from the 450 nm reads. Lines of best fit and standard curves were fit from standards in Excel and concentrations were inferred. The mean intra-assay coefficient of variation was 2.0%. The inter-assay coefficient of variation was 6.17%.

Viral manipulation study

Viruses

Rhabdomys Asip coding exons (accession JANHMN010000002; see sequence in Supplementary Methods) were cloned and packaged into an AAV (serotype 2/9) overexpression vector by the Princeton Neuroscience Institute Viral Core Facility at Princeton University. For Agouti overexpression, we generated AAVs carrying pAAV-hSyn-Agouti-T2A-eGFP-WPRE (titre 1.8 × 1014 genome copies per ml). This plasmid, pAAV-hSyn-T2A-eGFP-WPRE, has been deposited at Addgene (plasmid no. 246599). As a control, we generated nearly identical vectors lacking the Agouti transgene (pAAV-hSyn-eGFP-WPRE; 2 × 1014 genome copies per ml). pAAV-hSyn-eGFP-WPRE was a gift from J. M. Wilson (Addgene plasmid no. 105539). An hSyn promoter was selected to confer neuronal specificity. Efficacy of the viral transfection was confirmed with RNAscope with probes designed for Agouti and eGFP (above). Successful translation of ASIP was confirmed through immunohistochemistry for eGFP (1:2,000 dilution, Aves laboratories, GFP-1020) and ASIP (1:250 dilution, ASIP Polyclonal Antibody, Invitrogen, PA5-77052) using the immunohistochemistry method described above. To validate the ASIP primary antibody, we applied whole mount immunohistochemistry to sections of skin (150 µl) taken from the flank and light stripe of a PND4 African striped mouse, regions with known patterns of ASIP expression within the dermal papilla. To accommodate tissue differences, free-floating sections were processed in 12-well plates with otherwise identical reagents, reagent concentration and incubation durations as described in the method for immunohistochemistry given above.

Stereotaxic surgical procedures

Adult sexually naive males were tested a priori in a pup interaction test. Mice selected for viral manipulation and were randomly assigned to either Agouti overexpression or control GFP groups. AAVs were infused into MPOA bilaterally by stereotactic surgery. Anaesthesia was initiated with an intraperitoneal injection of ketamine (100 mg kg−1) and xylazine (10 mg kg−1) diluted with sterile saline. After 10 min, mice were fitted into a dual-arm stereotax with ear bars and maintained on 0.5–1.5% isoflurane in oxygen through a nose cone for the duration of the surgery. To target MPOA, two Hamilton syringes were angled inwards at 12°, centred at Bregma and lowered to anterior–posterior +1.35 mm, medial–lateral ±1.42 mm, dorsal–ventral −5.8 mm. Then 150 nl of virus was infused per side and allowed to absorb into tissue for 10 min before slowly removing syringes. Following surgery, mice were given a single, subdermal dose of Ketoprofen (10 mg kg−1) and bupivacaine was topically applied to the incision site. Bupivacaine was applied again 24 h postsurgery. Mice were provided with a single pack of Diet Recovery Gel (ClearH20, SKU 72-06-5022). Recovery was monitored for 5 days postsurgery. Pup interaction tests were conducted 1 week and 3 weeks postinjection, after which mice were euthanized, and brain tissue was fixed by use of transcardial perfusion. Viral injection site locations were confirmed with immunohistochemistry for the eGFP tag (primary Ab, Aves Laboratories GFP-1020; secondary Ab, JacksonImmuno Research 703-545-155). Mice for whom Agouti overexpression was off-target were included in the control group. Initial efficacy of viral overexpression was determined with RNAscope, as detailed above. A full protocol for these surgical procedures is available on GitHub (https://github.com/fdrogers/stripedmouse_parental_2025.git).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this