Rivers are expected to follow the path of least resistance. Yet in northeastern Utah, the Green River slices through hard limestone and sandstone at Split Mountain and the Canyon of Lodore instead of diverting toward softer shale and mudstone to the west. The formation of this route, which stretches for more than 100 miles across the Uinta Mountains, has remained a geological mystery for over a century.

The Uinta range rises to about 13,000 feet (4,000 meters) and formed roughly 50 million years ago. Evidence shows the Green River has only followed its current course for fewer than 8 million years, and possibly as recently as 2 million years ago. That mismatch in timing has long challenged earlier theories about how the river established its course.

A 150-Year-Old Puzzle in the Uinta Mountains

On June 22, 1869, American geologist John Wesley Powell camped on an island in the Green River and offered the first known attempt to explain the anomaly. He proposed that the river predated the mountains and cut its channel as the land uplifted around it, a concept known as a superposed stream. Powell wrote that “proof is abundant that the river cut its own channel; that the cañons are gorges of corrasion.”

Subsequent research raised doubts about that idea. The Uintas are about 50 million years old, while dating suggests the river began flowing along its present path around 8 million years ago, and possibly as recently as 2 million years ago. As Adam Smith, a researcher in numerical modeling at the University of Glasgow, told Live Science, “It’s such a weird path.” He added that the age discrepancy makes it difficult to support the idea that the river simply predates the mountains.

Other explanations emerged. One hypothesis suggested the Yampa River, south of the Uintas, eroded northward and carved a channel through the range that the Green River later adopted. Smith told Live Science this would have required a tremendous amount of force from a river that “isn’t particularly big,” noting that if such a mechanism were common, similar canyons would cut through many mountain ranges, which they do not.

Another theory proposed that sediment buildup temporarily elevated the Green River, allowing it to overtop the mountains. But according to Smith, the sediments present in the region are not as high as the Canyon of Lodore’s 2,300-foot (700-meter) walls, weakening that scenario.

The Lithospheric Drip Hypothesis

In a study published Feb. 2 in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface, Smith and his colleagues argue that the Uinta Mountains themselves subsided before rebounding, enabling the river to flow across them. According to the researchers, a process called lithospheric drip may have lowered the mountains enough to create what Smith described as “the path of least resistance.”

Lithospheric drips occur beneath mountain ranges, where Earth’s crust meets the mantle. The weight of mountains increases pressure at the base of the crust, forming dense minerals such as garnet that are heavier than surrounding mantle rocks. Over time, these minerals accumulate into a high-density blob that can detach and sink into the mantle. As it pulls downward, it drags the overlying crust with it, reducing surface elevation. When the blob finally breaks off, the landscape rebounds upward.

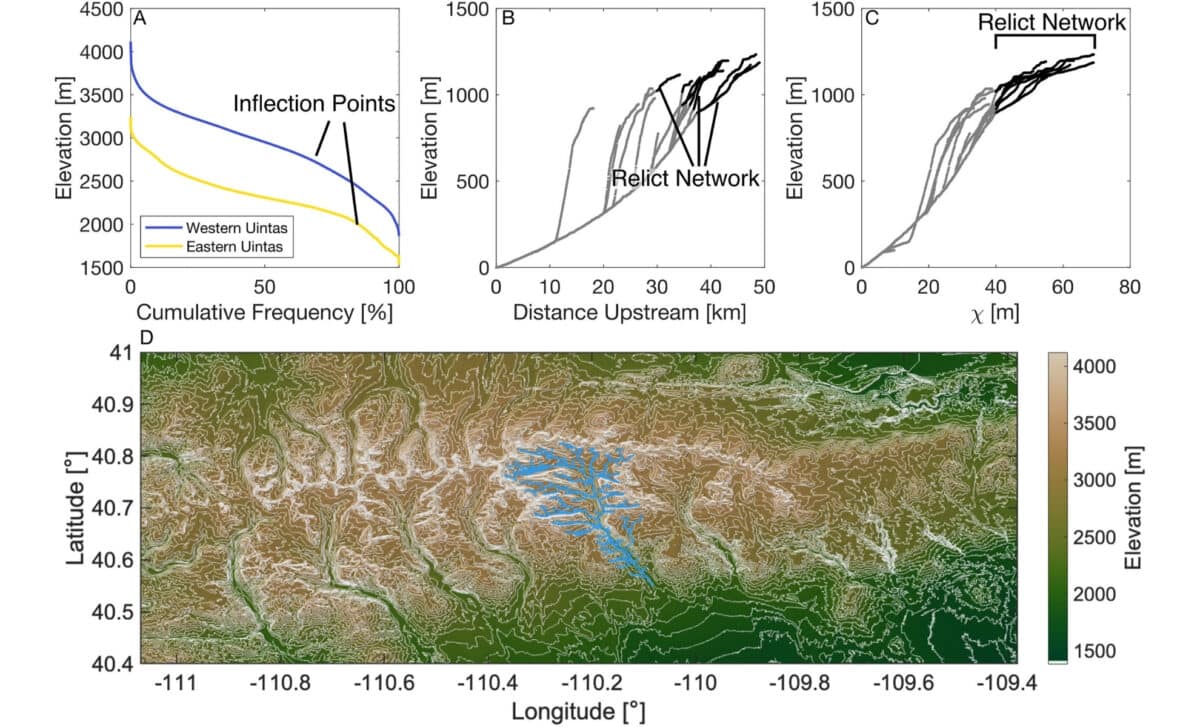

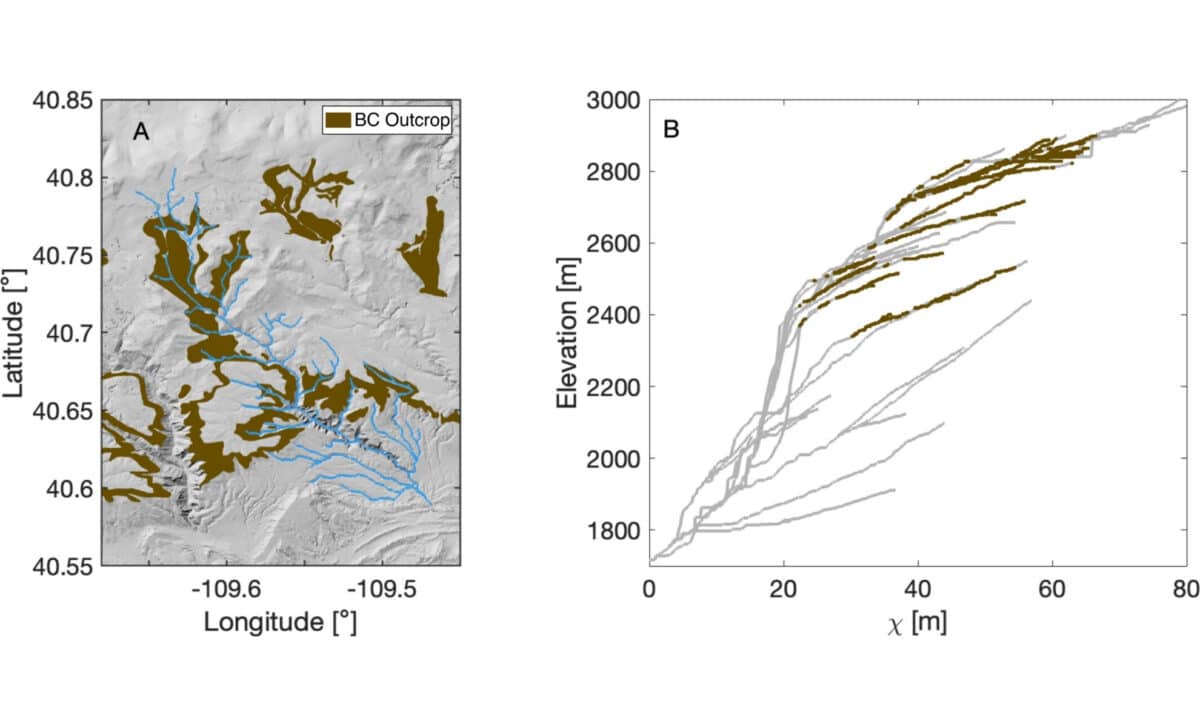

Smith explained in a press statement that lithospheric drip is a relatively new concept in geology, though evidence has been identified in places such as the Andes. “They can happen wherever you have had a mountain range form, and they can happen at any time,” he said. A distinctive bullseye-like pattern of uplift at Earth’s surface is considered a hallmark of this process. Smith’s team modeled geological processes in the Uintas using unusual river profiles and identified such a pattern.

Seismic Images Reveal a Deep Anomaly

To test their hypothesis, the researchers analyzed seismic tomography images, three-dimensional maps of Earth’s interior generated from seismic waves. They identified a blob roughly 120 miles (200 kilometers) deep beneath the Uinta Mountains that closely resembled an ancient lithospheric drip.

While examining what Popular Mechanics described as essentially a planetary-sized CT scan, the team also found that the crust beneath the Uintas was thinner than expected for a mountain range of its size. That thinning provided another indicator consistent with lithospheric dripping.

Using the observed drip’s depth and size, the researchers estimated that it likely detached between 2 million and 5 million years ago. This timing aligns with model predictions for when the mountains would have rebounded and matches estimates for when the Green River began cutting through the range.

Once the mountains subsided, the Green River could flow across them. As Smith told, after the river established that course, it continued incising into the rock, carving features such as the Canyon of Lodore.

Outside experts have described the explanation as plausible. Mitchell McMillan, a research geologist at the Georgia Institute of Technology who was not involved in the study, told Live Science that lithospheric dripping offers a credible mechanism for the river’s route. He added that the study’s most exciting aspect is its use of surface clues to understand mantle processes and their impact on mountain belts, calling it “a valuable demonstration of such an approach,” regardless of whether the drip hypothesis ultimately proves correct.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this