The coming decades of space exploration hinge on a single, stubborn number: the 225 million kilometres between Earth and Mars. Chemical rockets, the workhorses of every space programme to date, take roughly eight months to cover that distance. Russian researchers now claim they can shorten the journey to 30 days using an engine that turns hydrogen into a high-speed plasma beam.

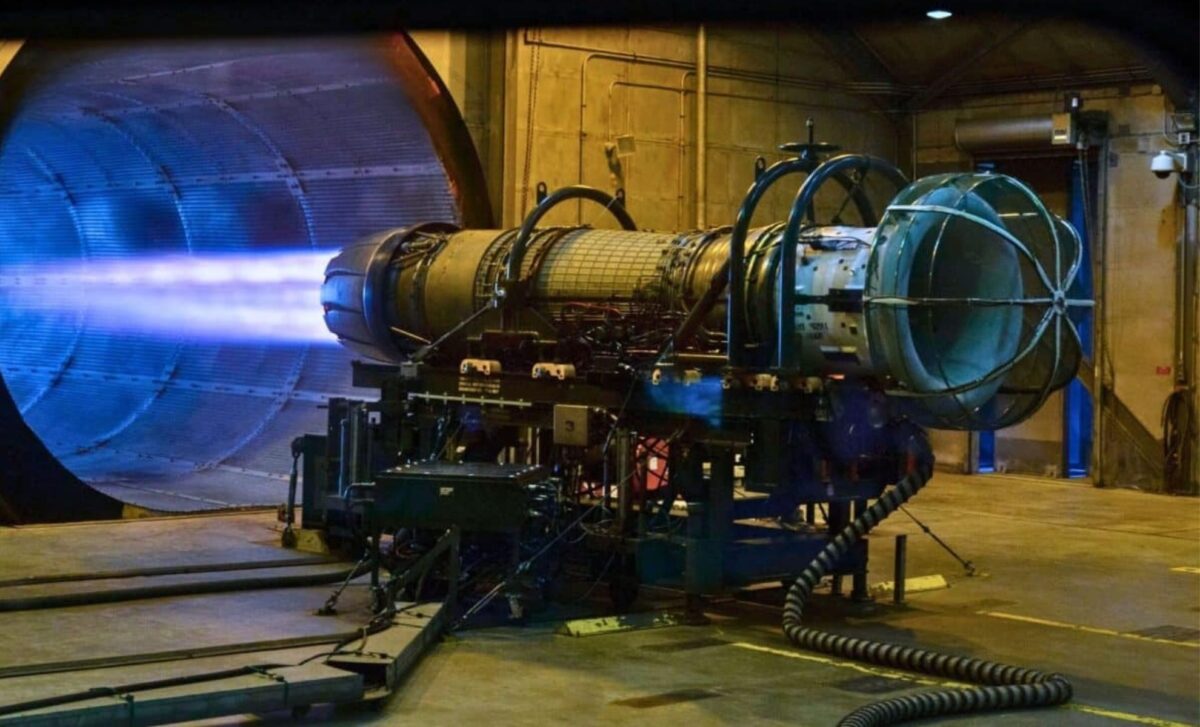

The propulsion system, developed by state nuclear corporation Rosatom‘s Troitsk Institute near Moscow, is undergoing ground trials inside a 14-metre vacuum chamber designed to replicate deep-space conditions. If the technology performs as its creators project, it would not only shrink interplanetary travel time but also fundamentally alter mission planning, spacecraft design, and the strategic calculus of governments competing for influence beyond low-Earth orbit.

The stakes extend beyond speed. A faster transit means crews spend less time exposed to cosmic radiation and microgravity, two of the most intractable health risks in human spaceflight. It also opens the door to routine cargo deliveries and, eventually, a sustainable human presence on another world. But the engine’s dependence on an onboard nuclear reactor and its unusually low thrust raise questions about whether laboratory results can translate into a flight-ready system within this decade.

A 100-Kilometre-Per-Second Exhaust Plume

The magnetoplasma accelerator propels charged particles – protons and electrons – to a velocity of 100 kilometres per second, based on statements by Alexei Voronov, First Deputy Director for Science at the Troitsk Institute. Voronov told Izvestia that in traditional power units, the maximum velocity of matter flow is about 4.5 kilometres per second, a limit imposed by fuel combustion conditions. In the new engine, he explained, the working body consists of charged particles accelerated by an electromagnetic field.

Konstantin Gutorov, the project’s scientific adviser, said the prototype operates in pulse-periodic mode at approximately 300 kilowatts. Gutorov added that earlier work had justified an engine life of more than 2,400 hours, which he described as sufficient for a transportation operation to Mars. The current testing phase aims to demonstrate the prototype’s performance in that pulsed mode.

Egor Biriulin, a junior researcher at the Troitsk Institute, outlined the basic mechanism. He said the engine relies on two electrodes: charged particles pass between them while high voltage is applied, creating a magnetic field that pushes the particles out. The plasma thus receives directional motion and produces thrust. Biriulin also noted that the engine does not require extreme plasma heating, which limits wear on components and allows electrical energy to be converted almost entirely into motion.

The projected thrust is about 6 newtons, which Biriulin described as the maximum among projects currently under development. With such characteristics, he explained, an interplanetary ship would need a reserve of time for acceleration and braking, meaning the flight would consist largely of smooth acceleration followed by deceleration.

Why Hydrogen and a Nuclear Reactor Go Together

The engine is not designed to lift spacecraft from Earth’s surface. Launch vehicles with conventional chemical propulsion would deliver the vehicle to low-Earth orbit, after which the plasma system would activate for interplanetary cruising. An onboard nuclear reactor provides the sustained electrical power required to maintain the electromagnetic field and accelerate particles. The working fluid is hydrogen.

Biriulin cited two advantages of hydrogen: its atoms are light, allowing significant speeds without large consumption of working substance, and it is the most abundant element in the universe, which could eventually enable in-situ refuelling. Rosatom officials anticipate that a flight model of the unit will appear in 2030.

Engines With a Proven Pedigree

Nathan Eismont, a leading researcher at the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, told Izvestia that Russian-made plasma devices already serve as thrusters for orbiting, manoeuvring and deorbiting satellites in the OneWeb constellation. He also noted that NASA’s Psyche asteroid mission, launched in 2023, carries Russian plasma engines.

Eismont emphasised that typical jet speeds for existing plasma engines range from 30 to 50 kilometres per second. The Troitsk development, he said, is ahead of the curve, and speeds of about 100 kilometres per second combined with hydrogen as a working body would bring the global space industry to a qualitatively new level. Recent analysis from TechSpot places this Russian work within the broader context of next-generation deep-space propulsion systems being pursued by the United States and China.

What Stands Between the Lab and Mars

The 2030 target for a flight-ready prototype depends on successful completion of ground tests, sustained funding and external validation of performance claims. No peer-reviewed data have been published, and the system has not yet operated in space.

Space-qualified nuclear reactors are rare. Launching fissile material requires approval from national and international regulatory bodies, and Rosatom has not released details of the reactor design intended for the engine. Integration into a crewed spacecraft would demand solutions for thermal management, radiation shielding and power distribution at sustained high output, areas where engineering challenges remain unresolved.

In mid-2025, Igor Maltsev, head of RSC Energia, publicly criticised the condition of Russia’s space industry, warning that expectations had outpaced realistic capabilities. His remarks underscored the gap between laboratory demonstrations and operational hardware.

The Global Race to Shorten the Journey

The Russian effort coincides with similar work elsewhere. NASA has invested in the Pulse Plasma Rocket and the Variable Specific Impulse Magnetoplasma Rocket, developed by Ad Astra Rocket Company in Texas. Both designs, as noted by TechSpot, aim for Mars transits of 45 to 60 days.

China’s Xi’an Aerospace Propulsion Institute reports developing a high-thrust magnetic plasma thruster, based on state media accounts. Researchers at Wuhan University are exploring how similar ionised-gas technology could improve high-altitude aircraft engines, potentially enabling plasma-based thrust within Earth’s atmosphere.

The concentration of resources on plasma propulsion across multiple countries reflects a shared judgment: chemical rockets opened access to space, but reaching other planets within practical timeframes will require a fundamentally different approach. Rosatom expects to complete a flight prototype by 2030, though the schedule depends on successful testing, sustained financing, and independent validation of the engine’s performance claims.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this