Sign up for the Slatest to get the most insightful analysis, criticism, and advice out there, delivered to your inbox daily.

On a recent stay at a friend’s house, I encountered a familiar problem. The friend, a thoughtful host, had left us washcloths, shampoo, body wash, toothpaste, and towels. She’d set out a bottle of filtered water and plastic cups. But when I stepped into the shower, I discovered that she had not given us what once would have seemed like a basic personal-care necessity: a bar of soap.

I wasn’t surprised. Bar soap is passé, replaced in the American shower by shower gels, facial cleansers, and silicone loofahs. These days, bathroom sinks rarely feature a ceramic tray with a half-used bar of Dial; instead, we treat ourselves to pumps of Coconut Linen or Iris Agave. Hotels, once reliable suppliers of individually wrapped bars, now bolt to their bathroom walls refillable liquid-soap dispensers.

“Body wash is outpacing bar soap in growth and consumer preference,” Brian Sansoni, of the industry group the American Cleaning Institute, told me. Over the coming decade, bar soap sales are projected to grow at a rate 21 percent lower than those of body wash, according to Sansoni. And bar soap skews old: About 54 percent of older Americans use solid soap, but only 22 percent of consumers ages 18 to 34 do.

In this era of peak skin care, the humble bar of soap seems like a utilitarian cleaning tool, not a bespoke cleansing solution. Rubbing some communal chunk of who-knows-what on your own personal skin? Madness. So undesirable is bar soap that at my local CVS, the store doesn’t even bother to lock it behind glass, unlike every other personal-care product. After all, only grandpas would steal it.

But I love bar soap. I find it the most efficient, effective way to clean my filthy body. I love the way it feels when it lathers up in your hands, and that you can always see just how much soap you have left. I love that bar soap isn’t sold for $11.79 in a giant plastic bottle that will still be lying in a landfill when the sun explodes. I love bar soap so much that I now bring my personal bar of soap, Irish Spring, with me on vacation, because I know that wherever I stay, they won’t have any. I carry my soap in one of those snap-top containers that you last used when you went to summer camp.

What will I do if my trusty Irish Spring goes the way of 19th-century patent medicines? It seems to be a haunting possibility. So I set out to learn everything I could about bars of soap and the modern body washes threatening to eliminate them. My adventure led me to the 19th-century birth of American cleanliness, to the woman in charge of the Irish Spring account at Colgate-Palmolive, to a particularly evil and destructive episode of Friends, and to a bacteriological laboratory where scientists-for-hire made a stunning discovery about soap I brought from my bathroom. I wanted to know if I was as obsolete as my favorite bath product. What I found is that our prejudices about what we keep in the shower—about what keeps us clean—go far deeper than the skin we scrub.

In his entire life, Louis XIV took only two baths. In many ways, the Sun King was an unusual person of the 18th century; he did, after all, rule France for 72 years. But in his bathing habits he was quite typical, writes Peter Ward in his indispensable The Clean Body. For most of human history, Ward makes clear, “bathing was highly exceptional, washing irregular, and cleanliness mostly a matter of appearances.”

This was true across classes. Samuel Pepys, whose diaries give us our clearest picture of 1600s middle-class life in London, was aghast when his wife suddenly got interested in bathing; only when she refused him entry into the marital bed for three days did he grudgingly consent to a wash. The majority, who mostly lacked easy access to fresh, warm water—or private bathrooms to use it—rarely washed, and almost never experienced a full-body immersion. If you felt the need to scrub a body part, you filled a pot with cold water and applied it selectively. (Even into the late 1800s, Degas painted and sculpted quite a few women doing just that.)

A robust set of folk beliefs even justified dirtiness. Lice, for example, were known to clean the blood of ill humors. The odors of peasants were expressions of their natural vigor. Even when opportunities to bathe presented themselves, many people resented the process as much as Pepys did. Edwin Chadwick’s 1842 Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain noted that one pauper, forced to scrub off the dirt upon admittance to a poorhouse, complained that the indignity was “equal to robbing him of a great coat which he had had for some years.”

Across the ocean, some American wives and mothers, in the pioneer tradition, made their own soap. But the evidence suggests that even in Colonial times, soap was typically purchased rather than made by hand. Manufactured in 10-pound blocks, soap was cut and wrapped at the grocery for individual customers. It was a utilitarian product, that is to say, sold by the ounce and used primarily for scrubbing underclothes.

A bevy of factors slowly transformed popular thinking about cleanliness in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Cholera pandemics swept the globe in the 1800s, and confirmed, for many, the prevailing notion of how illness spread in those years: miasma theory. Before germs were discovered and understood, “all smell was disease,” explained Melanie Kiechle, an environmental historian and the author of Smell Detectives: An Olfactory History of Nineteenth-Century Urban America. “Illness was caused by bad airs. Particularly bad smells were a sign that there was something in the air that could be dangerous.” (You might think the same, if you saw your neighbors die from cholera, which causes explosive diarrhea.)

“People protected their health by trying to change the air,” Kiechle said. She pointed to the example of window boxes, to which I had never given a second thought, but which were added to city homes in this era as part of a disinfectant regime. “People were afraid the air would make them sick, so they planted particular plants in their window boxes.” Rosemary, for example, or mignonette, might sweeten foul air before it entered the home.

What they didn’t do, though, was wash their bodies all that much. It was effluvia from decomposing corpses or sewage that concerned believers in miasma theory, not body odor. “The way that they reacted to body odors was not objecting that someone was filthy, or having a moral judgment, but that the way they smelled revealed the kind of work they did,” Kiechle said. “There was an olfactory hierarchy to the work that people did in, say, the stockyards. The worst jobs were the worst-smelling.”

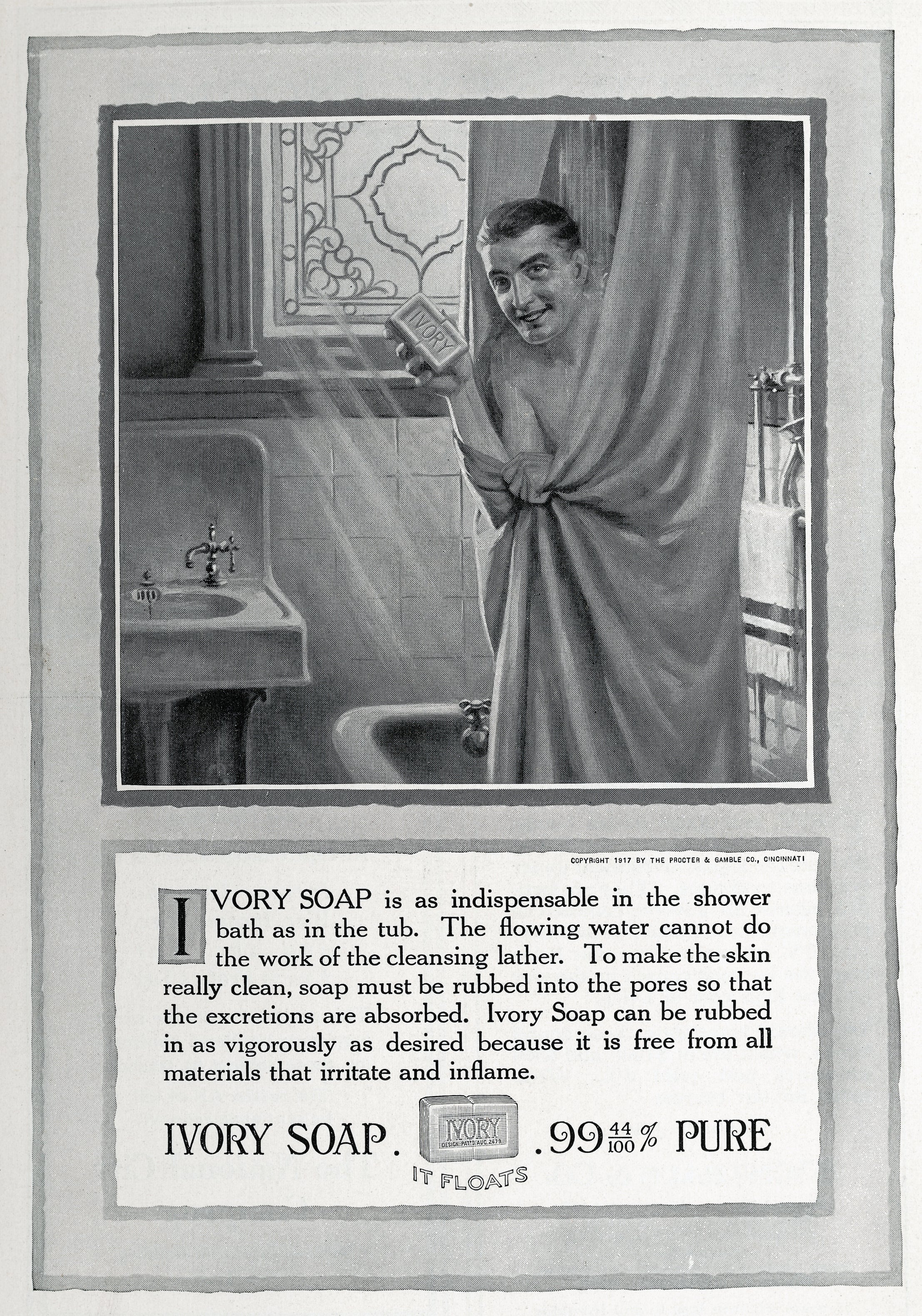

Bettmann/Getty Images.

As the growing bourgeoisie strove to separate itself from the working class, though, people started to consider how they smelled as one way to mark that distinction. The soap industry, its small soapworks rapidly consolidating into multinational corporations, launched new products designed to appeal to that anxiety, often through imagery linking whiteness to purity. In 1879, Procter & Gamble introduced Ivory Soap, attractively packaged in individual 9-ounce bars, and soon advertised the product as “99 44/100% Pure!”

“Pure of what?” asked Nancy Tomes with a laugh. Tomes is a history professor and the author of Remaking the American Patient: How Madison Avenue and Modern Medicine Turned Patients Into Consumers. “It was a time of extraordinary race science. ‘100 percent pure’ means … white.” As immigration boomed, the American upper class became “obsessed with cleanliness,” she said. “We had all these smelly ‘others’—we had to protect ourselves from them, and we had to clean ’em up.” Around the country, a “sanitarian” movement encouraged washing among children and the lower classes. From this era comes the popular image of a schoolteacher chastising a student for not washing behind his ears. But this focus on cleanliness alienated poor students at a time when few, still, had access to running water. In 1893, only 3 percent of families in New York had bathrooms. Yet near the turn of the century, the muckraking journalist Jacob Riis saw a Lower East Side teacher ask her class, “What must I do to be healthy?” In response, the children recited a laundry list of opportunities to which none had regular access:

I must keep my skin clean,

Wear clean clothes,

Breathe pure air,

And live in the sunlight.

At the same time, germ theory was finally becoming much more widely understood. “That was just huge in amping up the American cleanliness obsession,” Tomes said. “It’s one thing to have Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch say there are germs. It’s a completely different project to convince every American of every age that germs are real and they need to protect themselves against them.” Into this difficult project stepped the new multinational soap companies: Procter & Gamble, Colgate-Palmolive-Peet, Unilever, and Henkel, who between them controlled more than half of all soap production in the Western world. “Ninety percent of that convincing came from the marketplace,” Tomes said. “It was companies that realized that scaring people about germs sold product.” So lucrative was Ivory, for example, that when P&G built an enormous factory and R&D lab in St. Bernard, Ohio, it was named “Ivorydale.”

Soap companies at this time were advertising innovators, devoting unusually large proportions of their budgets to marketing. A turn through the pages of fin-de-siècle magazines, with their overabundance of soap ads, can remind one of the experience of watching television today and seeing nothing but insurance-company commercials. Ads focused on the health benefits of soap—especially after the introduction of Lifebuoy, one of the first antibacterial bars, in the 1890s—but also on the genteel and even romantic lifestyle that soap and its use might encourage.

As the new century progressed, a new incentive appeared for soap manufacturers to increase production: world war. One byproduct of the soapmaking process is glycerin. Once a waste chemical, glycerin had become valuable after Alfred Nobel pioneered the manufacture of the explosive nitroglycerin. With America’s entry into World War I, demand for explosives, and thus for glycerin, skyrocketed. As Shiqi Wang, a scholar of environmental history at Stony Brook University, explained to me, this upended the industry. “Soap itself became a kind of byproduct rather than the primary product,” Wang said. Procter & Gamble was suddenly a government-regulated weapons manufacturer, supplying a third of the glycerin made in the U.S. in 1918, Wang pointed out. The resulting surplus of soap depressed prices, so companies experimented further with adding perfumes and dyes to create a “refined” product for which they could charge more.

Sales of toiletries and cosmetics were nearly 20 times higher in 1950 than at the end of World War I. By midcentury, said Kendra Smith-Howard, author of the forthcoming The Dirty Environmental History of Cleaning Up, only a few rural Americans washed the way her parents had—once a week, in a washtub, with all the kids sharing the bathwater from oldest to youngest. Americans commonly understood that a modern person washed frequently, for reasons of health, beauty, and manners. All that remained was for the infrastructure to catch up to the ideal. In the 1940s, half of American homes had bathrooms; by 1970, the figure was more than 90 percent. A nice bar of soap, a shower every day: That was the American way.

For Christmas this year, my wife gave me a bar of Lightfoot’s Pine Soap, made in a factory in Rhode Island and sold at Kenyon’s Grist Mill in the town of West Kingston. She was enticed by the Strategist’s description, which she even wrote in Sharpie on the wrapped package: “For the husband who’s finally ditching Irish Spring.”

I confess it had never dawned on me to consider ditching Irish Spring, the soap I had washed with since I graduated from baths to showers, somewhere around age 5. It was the soap my dad used, and at that age I certainly wasn’t going out to the Food Lane to buy some other soap, so Irish Spring it was.

While I like to think I have escaped many of the traps of traditional 20th-century masculinity, I have definitely spent my entire life believing that thinking about, or spending a lot on, personal-care products is fundamentally frivolous behavior. I understand that it is meaningful to other people to buy lots of products and spend lots of time on their skin-care regimen. But me? I look the way I look, and I smell the way I smell, and it is not worth my time or energy or hard-earned money to do much about it.

Yet despite my resistance to skin-care trends, I have moved away from my dad’s shaving cream (Barbasol) and deodorant (Speed Stick). Why am I so doggedly loyal to this resolutely 20th-century soap?

The soap was launched in Germany as “Irischer Frühling” in 1970, a time when Germans were utterly infatuated with Ireland, thanks to a popular memoir by Heinrich Böll. Sensing, perhaps, an opportunity in America, a country where more than 15 percent of the residents claimed Irish or Scotch-Irish heritage, Colgate-Palmolive introduced Irish Spring to that market in 1972. Ads for the product were absurdly hoary and “Oirish”—witness this one, in which American actor Martin Kove, better known as the evil sensei in The Karate Kid, wins an arm-wrestling contest and then washes his burly chest in the out-of-doors.* The ad culminates in an image burned into my memory: a tweedy poet type using his pocketknife to carve a scrap off the bar of Irish Spring, revealing the fine white marbling within.

Irish Spring settled in as a default dad soap, alongside Dial and Zest. (Women overwhelmingly used non-“deodorant” soaps like Dove.) By 1989, the Chicago Tribune’s marketing columnist George Lazarus reported that Irish Spring “lagged far behind” other soaps in sales, though it was prominent enough a name for Colgate-Palmolive to try it out for a deodorant rebrand. Irish Spring body wash debuted in 2007; the company redesigned the brand in 2022, changing the formula for the “classic scent” bar soap. (A very, very small amount of customer annoyance accompanied this formula change.)

What is that classic scent? “Woody,” said Marilla Vasarhelyi. “Citrus. Green. Pine. That invigorating fresh feeling, like taking a deep breath when you step outside.” Vasarhelyi is the marketing director of the Irish Spring line at Colgate-Palmolive, and she spoke with me to answer all my questions about the soap I’ve been using for 45 years. Like: Is it “Irish Spring” as in “a burbling spring in Ireland,” or “Irish Spring” as in “the season after Irish winter”? “The intent is Irish Spring as in a spring, the water feature,” she said. “One of the consistent elements on our packaging is that it all shows some kind of water—a waterfall, the ocean.”

Why, I asked, did the company’s ads always include someone carving a piece of the bar off with a knife? “I actually don’t know,” she said.

Another question: In what way, exactly, is Irish Spring Irish? “Oh,” she said. “We are inspired by the outdoorsiness—the landscapes, the rivers of Ireland. Not to get too stereotypical, but we also take inspiration from the heritage of the Irish people—hardworking, witty, a dry sense of humor. We try to bring that to life in our communications.”

In truth, there is nothing particularly Irish about Irish Spring. Surely that is among the reasons that Irish friends I ask about the brand have never heard of it. (I am reminded of new classmates at college assuming that I, a Milwaukee native, loved Milwaukee’s Best, a beer that in fact I had never seen for sale in Milwaukee—presumably because real Wisconsinites would be annoyed at the very idea.) At least one Irishwoman was irked enough by Irish Spring’s overseas popularity that in 1987 she launched a competing brand, Irish Breeze, with the backing of the Irish government’s women-in-business initiative. Peggy Connolly of Cork proclaimed that her soap would soon capture 15 percent of the Irish market. It did not.

Unusually among soap companies, Irish Spring still sells more bar soap than body wash. “We’re a leading player in the bar category,” Vasarhelyi said. “Body wash is a bigger category, and we’re newer in that.” I asked if bar soap, these days, is an unsexy career path. Do the body-wash people sniff at the bar-soap people? “Bar soap is still in the conversation,” she insisted. “We’ve seen a little bit of a renaissance in the bar category. You can spend $60 on really elevated bar soaps from super prestige brands.”

I told Vasarhelyi that my dad washed with Irish Spring. “Mine too,” she said. “I remember watching him get ready for work—shaving, doing his combover with the gel. I would sit on the floor of the bathroom, and the bathroom smelled like Irish Spring.” Irish Spring may be a dad soap, she noted, “but then it becomes the kid’s soap. It transitions to the next generation, like it did with you. We’re trying to facilitate that.”

Lathering up with Lightfoot’s, it was easy to tell that it was comparatively luxurious. FRAGRANT AS THE BREEZE FROM THE PINES, read lettering pressed into the soap’s surface. Lots of pine in the men’s soap space! But Lightfoot’s was fresher, realer-smelling, less insistent than Irish Spring’s version of pine, which is so overwhelming that it’s known to serve as a pest repellent. A hundred and fifty years after Civil War nurses hung evergreen garlands in hospitals to ward off miasma, the scent of pine still feels more than clean—it feels refreshing, hearty, healthy.

But was this really my future? I liked this bar of soap, but it cost $10. Ten dollars for a bar of soap! If I buy Irish Spring at Costco, I’m paying 60 cents a bar. Am I not a dad?

It seemed to me, as I thought about it there in the shower, pinier than I’d ever been, that washing my body—my actual self—is a more private act even than brushing my teeth or putting on deodorant. In the shower I am communing with myself, giving precious attention to my physical form in all its glory: every chest hair, every weird mole, every farmer’s tan line. The act of washing, repetitive and ritualistic, is meditative, and spurs a sort of reverie. Here I am, I am reminding myself.

The soap I use has been an unexpectedly important part of that self-identification for a long, long time. My clothes change. My hair has disappeared. I lose weight and gain weight. But something of my essence, the air about me, remains consistent. If forced to put it into words, I might have described my loyalty to Irish Spring as admirable in its way—akin to my steadfastness as a friend, husband, and father. Surely it was comforting to my loved ones to know that no matter how dire the news, how terrible the world outside, Dan Kois would smell the same as he always has.

Maybe my wife wanted the novelty. “You do smell different,” she said after my shower.

“Is that why you bought it for me?” I asked. “You just wanted me to smell different?”

“Oh, I don’t know,” she said. “I just look at those bars of Irish Spring and they’re so green.

I know they all have chemical colors or whatever, but it seems so artificial.”

“It’s just Irish!” I protested. “Would you say a Shamrock Shake seems artificial?”

“Yes,” she said.

In 1979, right around the time I took my first shower with Irish Spring, a Minnesota entrepreneur named Robert Taylor had a brilliant idea. Taylor had left a sales job at Johnson & Johnson to launch a new company, the Minnetonka Corporation. For years, the company scratched out an existence manufacturing novelty bath products—lemon-shaped lemon soap, the kind of thing you’d give someone as a housewarming gift, and then they’d never use. His daughter later recalled that her dad would come home from work reeking of soap.

Perhaps for this reason, Taylor was frustrated with soap as a category. One day, driving to the office, “I thought how ugly bar soap is, and how it usually messes up the bathroom,” he later told the New York Times. It was almost the 1980s. Couldn’t soap look a little nicer? What if it didn’t come in a bar at all?

Taylor, of course, wasn’t the first to make liquid soap. Among many others, Emmanuel Bronner had manufactured and sold his “Magic Soap,” the bottles festooned with quasi-religious tracts, since the 1940s. But while not all liquid soaps espoused the need to “unite spaceship earth,” liquid soap did, in the 1970s and 1980s, have something of a countercultural vibe. If you lived on a commune, you might use Dr. Bronner’s Peppermint or a product much like it to wash your hair, brush your teeth, and protect your garden against aphids.

Taylor was looking for something a little more upmarket. He experimented in his kitchen until he perfected a liquid soap that squirted from a pump with just the right consistency. He called it Softsoap. Fearing copycat competition from the multinational soap behemoths, he leveraged Minnetonka to the gills and ordered 100 million hand-pump bottles from the only two American companies that manufactured them. The pump guys told him the order was so huge that Softsoap would monopolize their lines for a year. At least if his old colleagues at J&J tried to steal his idea, Taylor figured, he’d have a head start.

Softsoap launched in 1980 with an $8 million marketing campaign. It was an immediate hit. I still remember visiting the houses of friends and seeing Softsoap in their powder rooms and thinking, Oh, this is how rich people wash their hands. Unlike a bar of soap, which once removed from its packaging could only ever be a bar of soap, Softsoap was the attractive packaging—the bottle was the product, just as much as the soap was. A relatively affordable status symbol, the Softsoap bottle cloaked soap’s utilitarian purpose in pastel gardenias or proud Scottish tartan.

Robert Taylor went on a real roller coaster ride: By 1981 his company’s revenues nearly quadrupled, but then he lost his pump-bottle monopoly. Nearly 100 competitors leapt into the liquid-soap game, and in 1983 Minnetonka had to lay off more than 200 employees. A price cut helped Softsoap regain its market leadership, and Taylor eventually sold the brand to Colgate-Palmolive. He went on to innovate in the fields of toothpaste and cologne—did you know that Calvin Klein’s Obsession was born in a Minneapolis suburb?—before selling Minnetonka to Unilever altogether for $376 million.

In retrospect, Softsoap was the beginning of the end for hard soap. Once corporations discovered people were willing to pay more money to avoid looking at soap at the bathroom sink, it was only a matter of time before they realized they could also charge people more money to avoid looking at soap in their showers. Body wash is a “syndet”—a synthetic detergent, which unlike many soaps often derives its cleansing power from petroleum byproducts. Already standard in European showers, body wash was introduced by the big American brands in the early 2000s, with Old Spice first to market in 2003 and Axe following in 2004.

Perhaps due to a belief that women were pickier in the shower and would be less likely to switch from their trusted Dove, the early American brands were male-focused and male-marketed, their charcoal-gray bottles adorned with ripped abs. Fearing men would reject the dainty pouf, bath companies conjured a new product category from thin air: the hypermasculine “shower tool,” a scrubber embedded in industrial-grade black plastic—a nod to utility that inverted the wife-coded aesthetics of Softsoap.

It worked. Young men defected en masse, and sales of deodorant soap fell by 40 percent. In 2009, body wash sales exceeded those of bar soap for the first time. An Ad Age story marking the achievement noted that the bar soap category had so diminished that P&G, Colgate-Palmolive, and Kao Brands had all outsourced their flagship deodorant soaps (Zest, Irish Spring, and Jergens) to the storied Ivorydale plant in Ohio. The “ancestral homeland of bar soap in the U.S.” was now owned by a Canadian contract manufacturer. “The thought of those rivals co-mingling under the same factory roof,” wrote Ad Age, “would once have sent shivers up the spine of … veterans of the 20th century’s storied bar-soap advertising wars.”

It was around this time that the great hotel migration away from bar soap began. It was once standard operating procedure for hotels—from the lowliest Motel 6 to the priciest resort—to stock guest bathrooms with a miniature bar of soap, alongside airline-liquor-sized bottles of shampoo, conditioner, and lotion.

This was, indisputably, wasteful. A guest staying one night would leave the products half-used in the shower, where the housekeepers would find them and then toss them in the trash. But this bounty of amenities, hospitality in miniature, contributed to the sense that a hotel room was a kind of space outside the bounds of ordinary life. You’re not in your own bathroom anymore, these products said to the hotel guest. Conrad Hilton picked this soap out just for you. Oh, you’re stuffing the toiletries into your suitcase to stock your guest bathroom? Conrad doesn’t care. He’ll just deliver more the next day.

The hospitality consultant Charis Atwood has spent her 26-year career overseeing what the industry calls OS&E (operating supplies and equipment) and FF&E (furniture, fixtures, and equipment). Between 10 and 15 years ago, Atwood told me, hotels started moving away from single-serving bath products. “It started in limited-service properties, hotels that don’t have full restaurants,” she said—your La Quintas, your Hampton by Hiltons, your Holidays Inn Express.

These hotels, already serving a bargain-hunting customer, saw an opportunity to streamline operations and cut costs by moving the bath products to permanent pump fixtures, installed on bathroom walls and refilled by housekeeping. Initial rollout of this OS&E solution created FF&E dilemmas; the dispensers either had to be screwed into the shower, creating waterproofing problems, or stuck onto the wall with double-sided tape, which failed if the bottle was too heavy. But as the trend spread to full-service hotels, the wrinkles were ironed out. “When you’re building a new hotel or renovating an older one now, the dispensers get bolted into the showers by the contractors,” she said. “That’s standard.”

To hear the hotels tell it, this was a sustainability move customers could get behind. As Hilton’s vice president of supply management, Linda Theisen, put it to me, “It’s a win-win-win—a win for our business, a win for the environment, and a win for our guests.” And it is more sustainable, to be sure, to refill guests’ bath products rather than to throw away little bottles every morning, just as it’s more sustainable to cut housekeeping from daily to on request. But it’s hard to shake my certainty that what really drives hotels to make changes like this is saving money. That it’s incidentally good for the environment is a bonus. (Theisen did not respond to my question about the cost savings from refillable toiletries.)

Consumers often react poorly to having something they saw as a perk taken away. Perhaps to counter this resentment, even midrange hotels now offer brand-name, fancy (or fancy-seeming) products in their pumps. Malin + Goetz is stocked at Le Meridien hotels; I’ve seen products with Malin + Goetz–esque sans-serif lowercase logos in a Hampton by Hilton. (Thanks, Conrad.) The pumps serve as advertising not only for the brand of cleaning product but for the gestalt of the hotel itself. Is this hotel bright blue and yellow, ocean breeze and palm oil? Or is it stark black and white, lavender and peppermint?

Because I view communal bottles of bath products as evidence of cost-cutting, I’m always darkly convinced that what housekeeping fills the bottles with is somehow an inferior product. A laughable concern, I know. Oh, the guy who washes himself with Irish Spring at home is worried that his Days Inn is cutting his body wash with the cheap stuff? Atwood noted that during COVID, when everyone became hyperaware of just how many germs human bodies spread around, some hotels started installing locks on their dispensers, so you’d never be afraid that the previous guest had left something gross in the body wash. I now realize that in a hotel room with unlocked dispensers, a real sicko could wreak absolute havoc—something I certainly never worried about when I was unwrapping my individual bar of soap circa 2010.

In higher-end properties, Atwood said, the trend is away from wall-bolted pumps and toward standard consumer-sized bottles on shelves. “That just looks nicer,” she said. And many very nice hotels, she told me, still often supply bars of soap in addition to body wash. “Part of the luxury experience is that they offer it all,” she said. “Whatever your preference, it’s in the bathroom.”

As hospitality is redefined in hotels, so too is it redefined in our homes. When I told Nancy Tomes about my experience staying at my friend’s house, she observed that perhaps the friend was trying to replicate the hotel experience. Once, that would have meant a bunch of individual soaps, perhaps bars actually swiped from hotels during multinight stays. Now it means a bottle of nice body wash in the shower. “That’s what you’d see in a more expensive Airbnb,” Tomes said. As the Expensive Airbnb aesthetic takes over the American home—ever more spacious, ever whiter—the American bathroom, too, gets a hotel upgrade. Once upon a time, a new bathroom would include a porcelain soap tray jutting from the wall. Now, according to the Census Bureau’s American Housing Survey, more than 80 percent of new home builds include built-in liquid-soap dispensers in their showers or sinks.

Body wash’s ascendance seems complete, as bar soap clings grimly to a fading, aging audience. No longer a product targeted solely to quality-indifferent men, body wash now runs the gamut, with popular washes ranging from major brands’ basic lines to expensive, spa-quality cleansers.

The generational split in bath products especially haunted me as I contemplated the fate of my beloved bars. Nathan Simon—University of Massachusetts Amherst undergraduate, soapmaking entrepreneur, and the rare Gen Z bar-soap advocate—told me he’s had some luck with selling soap to his cohort by focusing on the health and lifestyle benefits. But he’s faced one especially stubborn and annoying belief held by young people: that the soap in your shower is dirty. One study revealed that 60 percent of consumers ages 18 to 24 believe that bar soap is covered in germs.

What has led to this anxiety? What is it about a soap bar that provokes not just fear but revulsion and disgust? We’ve all encountered a bar sitting in a dish with inadequate drainage; the viscous sliminess that results can be profoundly off-putting. It does feel, as you touch it, as though you’re handling not a cleaning product but an object bearing the secretions of some gross beast.

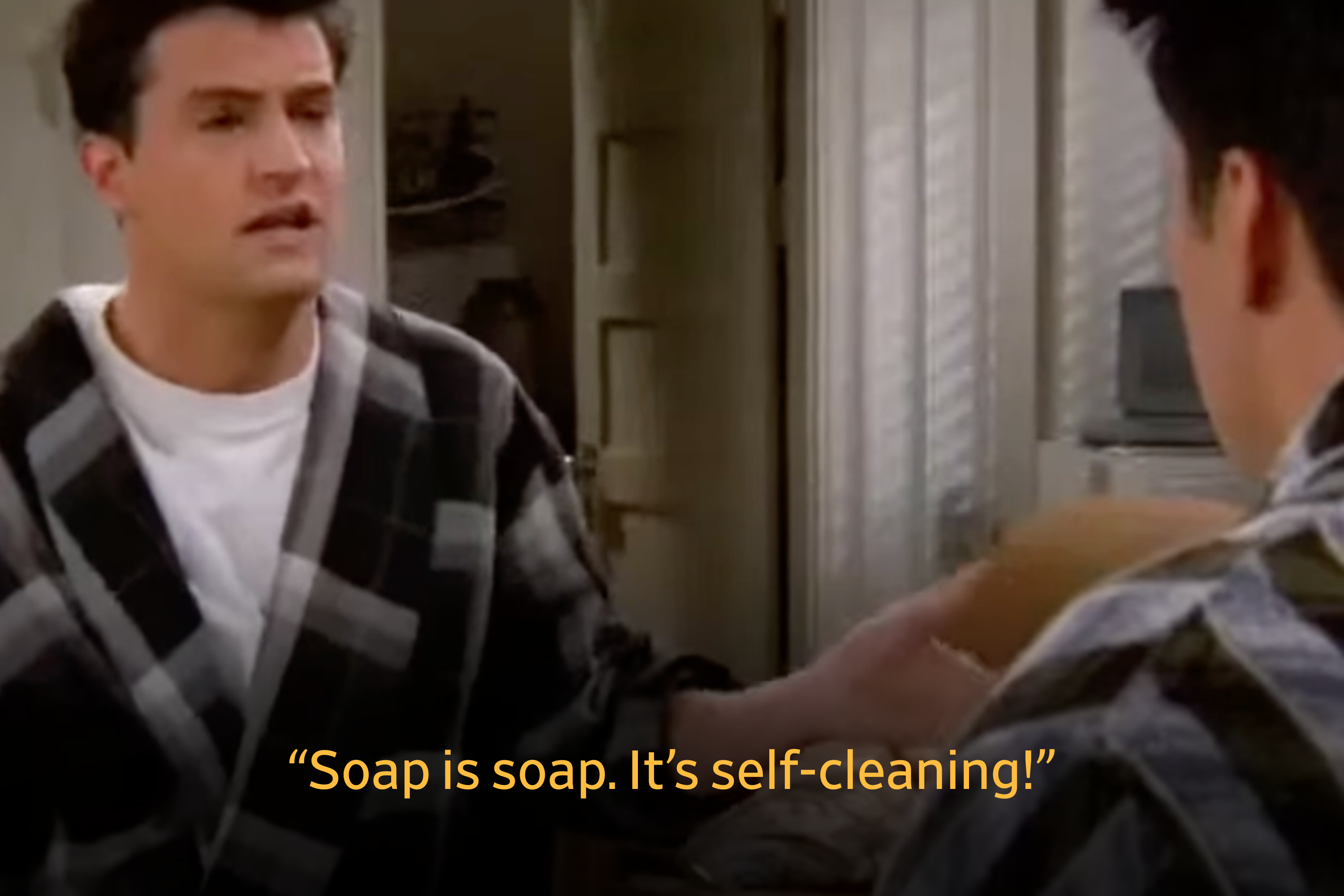

But I think there’s more to it than that. After all, older people have had more chances to handle slimy bars of soap, and older people don’t really share this fear. (In the same survey, only 31 percent of consumers over 65 worried about the dirtiness of bar soap.) Perhaps this generational disgust for soap comes from somewhere even more primal, the Rosetta stone of 21st-century America: the NBC sitcom Friends. Behold a scene from Season 2, Episode 16, “The One Where Joey Moves Out”:

Chandler—neurotic, fastidious Chandler—is angry about Joey using his toothbrush, but sees nothing wrong with sharing soap. “Soap is soap!” he protests. “It’s self-cleaning!” Joey sets him straight. “The next time you take a shower,” he warns darkly, “think about the last thing I wash, and the first thing you wash.”

This episode first aired in February 1996. Friends came to syndication in 1998, just a few years before the beginning of body wash’s ascent. A nation watched and rewatched this scene, weekdays at 5:30, and I suspect Chandler’s fear started to eat away at us. How widespread did this anxiety become, and how quickly? In 2007, Slate’s reader-favorite “Explainer” question was about the dirtiness of soap, and the specific phrasing of the question was telling (emphasis mine): “How clean is bar soap in a public bathroom? Is it ‘self-cleaning,’ since it’s soap?”

As the years went by, Friends only extended its reach. In 2014 the show came to Netflix, where it was watched so obsessively by millennials that the company paid WarnerMedia an extra $80 million just to extend the license one more year. And then Friends debuted on HBO Max in May 2020, the terrified peak of the coronavirus pandemic. We were washing our groceries, so frightened were we of germs. And what did America’s youngest streaming viewers—enduring day after day of Zoom school because if they left the house they would catch the plague—see on their laptop screens? Joey Tribbiani telling his roommate that he washed his ass with that soap. Friends and COVID, I fear, turned America’s young people into a generation of Chandlers, squicked out and shuddering with disgust.

Is this fear even warranted? My first response is: People are not rubbing the bar of soap on their butts, are they? We’re all lathering up our hands and using our hands to wash ourselves, maybe with a little soap boost now and then? Or we’re using washcloths, though I still do not like washcloths, despite once having been clowned for my preferences by a future Academy Award–winning screenwriter. When forced by a bar soap–abjuring hotel to use a washcloth, I can never help but notice just how many of my body hairs remain entangled in the weft of the cloth, impossible to rinse out.

What about the science? That Slate Explainer from 2007 noted that some studies did show that soap could accumulate bacteria. But experts believe that such bacteria pose little danger—that when you lather up a bar of soap and then rinse your hands, bacteria are cleaned and washed away. In one extremely dubious-sounding experiment conducted by P&G in 1965 and replicated by Dial in 1988, scientists coated bars of soap with E. coli and asked test subjects to wash their hands with them. Test results, these soap-company scientists claimed, showed that no contamination transferred from soap to hands. Still—yuck!

The soap advocates I spoke to pooh-poohed the very idea of soap being germy. “It’s nonsensical,” said Nancy Tomes. “It really overlooks the antibiotic properties that most soaps today have,” said Melanie Kiechle. “They’re bars of soap,” scoffed Irish Spring’s Marilla Vasarhelyi. “Their purpose is to clean.” Like a born marketer, she suggested that if a person is worried that shared soap is dirty, she should simply purchase her own bar.

“What about loofahs?” demanded Nate Simon. “Those are, like, breeding ground for bacteria.” Maybe they are, I thought. Those things just hang in showers, accumulating germs, right? It was time for an experiment that was not funded by a soap company. And that’s how I ended up in a bacteriological testing lab, toting wet bath products in Ziploc bags.

As has happened every time I’ve ever met a scientist who studies bacteria, Jonathon Hall offered a handshake when he met me—and then shortly afterward washed his hands.

“We’ve been talking about how we’re going to do this since you called us on the phone,” Hall, the director of microbiology at HP Environmental, told me as we stepped into the testing lab. Much of the Herndon, Virginia, consulting firm’s work involves testing water samples for contaminants, so the three solid objects I had brought in posed interesting logistical challenges. The lab tech, Elizabeth Lewis, laid out my three Ziplocs and labeled them 1, 2, and 3. Object 1: a plastic pouf that’s been hanging in our kids’ shower for an unknown number of years. They use it to wash, because they are young people, although it hasn’t gotten much use lately, because they’re away at college. In the interests of science, my wife had used the pouf that morning (with her bar soap).

Object 2: A half-used bar of Irish Spring straight from my bathroom. This bar of Irish Spring had really been through it. This bar of Irish Spring had seen some things. I’d scrubbed with it for a week’s worth of showers—yes, including my Tribbiani regions—and left it overnight in a sad little puddle in a soap dish. Then, using tongs, I transferred the soap into a Ziploc. Or rather, I tried to. It turns out that it’s very difficult to pick up a wet bar of soap with tongs, so after I dropped it on the floor of the shower, I slid it into the Ziploc with my hands.

“We’ll cut a small sample off the pouf, maybe 4 inches square,” Hall said. They’d place that sample in a tray of trypticase soy agar, a growth medium, and give it a few days to see what bacteria reproduced in the culture.

Lewis picked up the bag containing my slimy bar of Irish Spring. “For this, I think we’ll use a swab to take a sample from the bottom of the bar,” she said.

“Very lightly, just the surface,” Hall said. The goal was to capture whatever bacteria might reside on the soap without getting too much soap in the sample, because soap has antimicrobial properties—any soap Lewis collected on her swab would inhibit the ability of bacteria to reproduce. Soap, in a way, would be a contaminant in this particular scientific experiment. “If you’re going to try to make any kind of interpretation of these results,” he said, “you want to keep soap out of the sample as much as you can.”

Together, they eyed the third object I’d brought: a brand-new bar of Irish Spring, still in the box. “Probably there’s no germs on it,” I said, “but I figured the experiment should have a control.”

The scientists nodded, maintaining straight faces. “I guess we’ll just, like, swab this, too,” Lewis said.

“I suppose your testing will reveal that it’s mostly soap,” I suggested.

“Possibly so,” she said.

Lewis took the samples, smeared them into their new petri dish homes, and let ’em cook. It was a wild weekend in the HP Environmental lab, bacteria reproducing the nights away at 95 degrees. On Monday, Hall sent me the results in an email. Sample 3, the new bar of soap, exhibited no bacterial growth at all. In Sample 2, the used bar of soap, the lab found a bacterial plate count of 2,500 colony-forming units per square inch. And Sample 1, the scrubber? A veritable swamp: 43,000 colony-forming units per square inch!

“Looks like your hypothesis was correct,” Hall wrote. “Test results suggest that bacterial levels are lower on the soap compared to the body scrubber.”

Does this mean that hygiene-conscious young people should throw their shower scrubbers in the trash? No. This very general test didn’t, for example, identify the type of bacteria growing in those cultures. Some bacteria is good for your skin! But Hall said in a follow-up that the important finding here is that the test “indicated that the pouf can act as a reservoir and breeding ground for bacteria.” The main thing this test proved, to the extent that it proved anything, is that bar soap is less hospitable to bacteria. That’s great news! This is surely as true when soap and water encounter a dirty pouf as when they encounter, say, your human skin.

The purpose of this quasi-scientific experiment wasn’t to prove that shower poufs are disgusting. Instead, I hope that those young people who previously spurned bar soap because they felt it was crawling with germs might acknowledge that a bar of soap is no more dirty, and probably less dirty, than other items in their showers. Rebel against the cult of Chandler! Try a bar of soap!

If I was really going to rant for this long against body wash, I should at least give the actual product one more try. When I told my wife I was going to the store to buy a bottle, she said, “Ooh, what kind?”

“Irish Spring,” I said.

“Oh my God,” she said, throwing up her hands.

In the end, I purchased Native body wash because it appeared to be petroleum-free and its plain white bottle didn’t seem guy-coded. However, when it came time to choose a scent, my gender programming kicked in and led me to “sea salt & cedar” over “cotton & lily.” Still, if I only washed with it once, I thought my wife or daughters would might be willing to finish the bottle.

In the shower, I squirted a big old gloop on our one remaining pouf and lathered up. I found it less satisfying than usual to use the pouf on my arms and shoulders, and more satisfying than usual to use it on my legs and feet. I simply could not bring myself to wash my undercarriage with the pouf; instead, I squeezed lather on my hands and washed with those. I do not need those parts of my body exfoliated, even gently.

It wasn’t bad, using the body wash. It just wasn’t me. I felt that I didn’t rinse as clean, and it was striking just how many times I had to wring the pouf to get the suds out of it. (Thirty-four times, specifically. Maybe I used too much body wash.)

This surely had more to do with my preference than my actual experience. Indeed, Marilla Vasarhelyi told me that Irish Spring’s market research confirms that once someone’s established a cleansing routine, it’s very difficult to get them to change habits. But I will absolutely stand up for my own habit’s existence, its survival—and perhaps even its superiority.

Pretty much everyone I spoke to for this story scrubs with bar soap. Jonathon Hall, microbiologist, likes a nice farmers market soap with a fresh scent. Peter Ward, historian, is partial to an olive oil soap called Savoness. Charis Atwood, hospitality consultant, just feels she gets more clean with bar soap.

“I use bar soap, because I’m an environmental historian,” said Melanie Kiechle when I asked her what she stocks in her shower. (She’s partial to the Dove moisturizing bar.) In addition to objecting to the plastic bottles that will never be recycled and the petroleum byproducts swirling around the drain, she pointed out, “Many people who use body wash also use plastic loofahs, which are constantly shedding microplastics.”

But in addition to these real reasons, it was striking how many of the people I spoke to evoked comfort and nostalgia, even returning to their childhoods. The historian Kendra Smith-Howard uses bar soap because she, too, wants to avoid petrochemicals and plastic packaging. But she also wistfully recalled that when she was little, she and her cousin would pretend they were shaving their legs with a bar of soap. “It made us feel very fancy,” she said.

Where does bar soap go from here? Unlike an old bar of soap, the market isn’t dwindling to absolutely nothing. A recent report from Market Data Forecast acknowledged the headwinds for bar soap sales but pointed out that growing consumer interest in “authenticity, craftsmanship, and community-based production” has led to opportunities for small-batch, farmers-market soaps. The researchers note that Etsy and other platforms recorded a 68 percent increase in artisanal soap sales in 2023.

Several soapmakers I spoke to talked about the San Diego–based brand Dr. Squatch, founded in 2013, as a kind of beacon for bar-soap lovers. The company’s quirky ads both highlight the soap’s natural benefits and portray a certain kind of burly, sensitive 21st-century version of manhood. (Dr. Squatch men wear flannel, but also let their daughters braid their beards.)

The ads also hint at less verifiable product benefits. When Nate Simon, the collegiate entrepreneur, first encountered the brand, he recalled fondly, “their whole marketing campaign was toward teenage boys. ‘If you use this soap, ladies will love you and you’ll definitely get laid.’ Those ads definitely worked on me.” Recently, Dr. Squatch made a splash with a campaign featuring a limited-edition soap made from Sydney Sweeney’s bathwater; more recently, the company was bought by Unilever.

For most of the hobbyists and farmers-market soapmakers I spoke to, a sale to a multinational conglomerate for a reported $1.5 billion is not the plan. Inspired by the needs of her own sensitive skin, Vanessa Cochran has been cooking up lovely bars of soap since 2001 under the brand name Soap Farm. “It’s always been a side hustle,” she told me. She’s made her soap in an apartment on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, in a house in Los Angeles, and now in her kitchen in Arlington, Virginia. These days, she said, she sells 50 or so bars a month, a mix of her own favorite scents and bespoke bars for regular customers. Even Lightfoot’s, which surely benefited from that writeup in the Strategist, primarily sells its soap out of barrels in a New England general store. It’s a small piece of the portfolio of Bradford Soap Works, founded in 1876, which also manufactures aerosols, lotions, and syndets for brands like Neutrogena, Cetaphil, and Aveeno.

All these bar soaps are facing the same dilemma that Vasarhelyi told me Irish Spring grapples with. Nostalgia is bar soap’s great strength, but if you depend too heavily upon nostalgia, your brand tips into fogeyness. Exacerbating this problem is customers like me, whose only wish for Irish Spring is that it remain precisely the same as it was when I started using it 45 years ago—a consumer preference that, if catered to, is not likely to win a product many new users who aren’t the children of Irish Spring dads.

When I asked Vasarhelyi what she washes with, she noted that for professional reasons, her shower is complicated—it contains four body washes and five bars of soap, including Irish Spring prototypes and competitors’ products. But she feels an obligation to stand up for bar soap in these challenging times. “We’re passionate about bar,” she said. “It’s how we were born.” Then she launched into a reverie that unexpectedly captured, I think, what I still find so alluring about bar soap—whether it’s a deluxe product infused with the scent of the New England forest, or the 14th bar out of a Costco 20-pack.

“There is nothing more delicious,” she said, “than a brand-new bar of soap coming out of the package. It’s pristine. It’s unused. It’s smooth, unblemished. I find there to be something so inherently yummy about that.” She sighed. “Maybe, as a bar-soap user, you agree.”

You can keep your body washes with their magnesium or their tea tree oil, their exfoliants and emollients. I’m a bar-soap user. It’s how I smell. It’s who I am.

Correction, Feb. 17, 2026: This story originally misidentified the actor in a 1970s Irish Spring commercial. His name is Martin Kove; John Kreese is the character he would later portray in The Karate Kid.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this