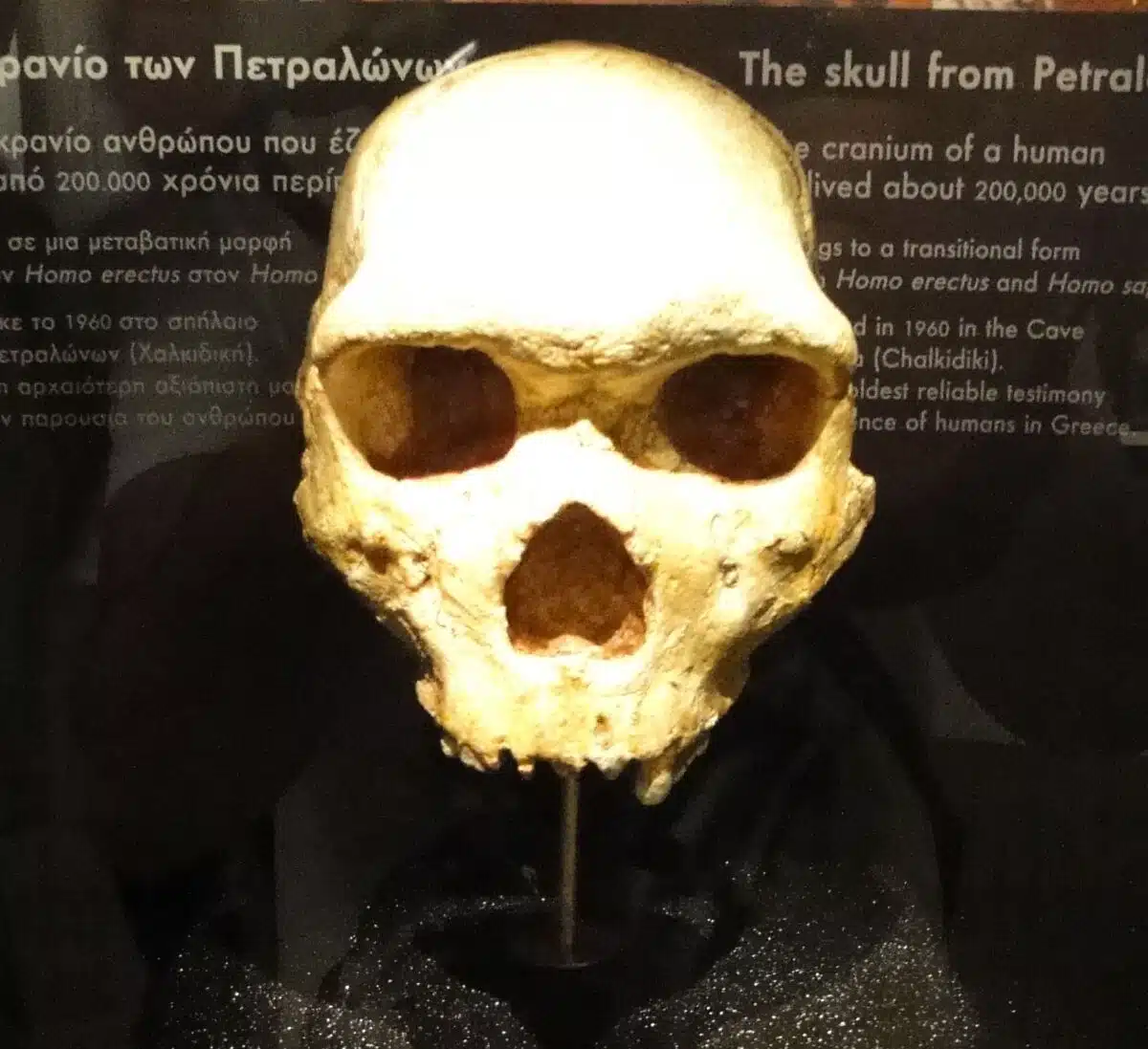

A human skull hung on a cave wall in northern Greece for more than 300,000 years. When a villager spotted it in 1960, cemented in place by mineral deposits, it launched a scientific mystery that would outlast most of its original investigators. The skull belonged to no one researchers could immediately identify.

It looked ancient, but not ancient enough. It looked human, but not human enough. For six decades, the Petralona cranium sat at the center of a dispute that touched on fundamental questions about human evolution. Was this an early Neanderthal, a late Homo erectus, or something else entirely. Without knowing its age, researchers could not place it in any family tree with confidence.

The range of proposed dates stretched from 170,000 years to 700,000 years, a span wider than the entire history of our own species. A fossil cannot be classified if its place in time remains unknown.

That uncertainty now has a resolution. As detailed in the Journal of Human Evolution, researchers have published uranium-series dates on the calcite crust growing directly from the skull. The results give the Petralona cranium a minimum age of 286,000 years and place it within a population that shared Europe with Neanderthals for more than 100,000 years.

Dating the Calcite Crust

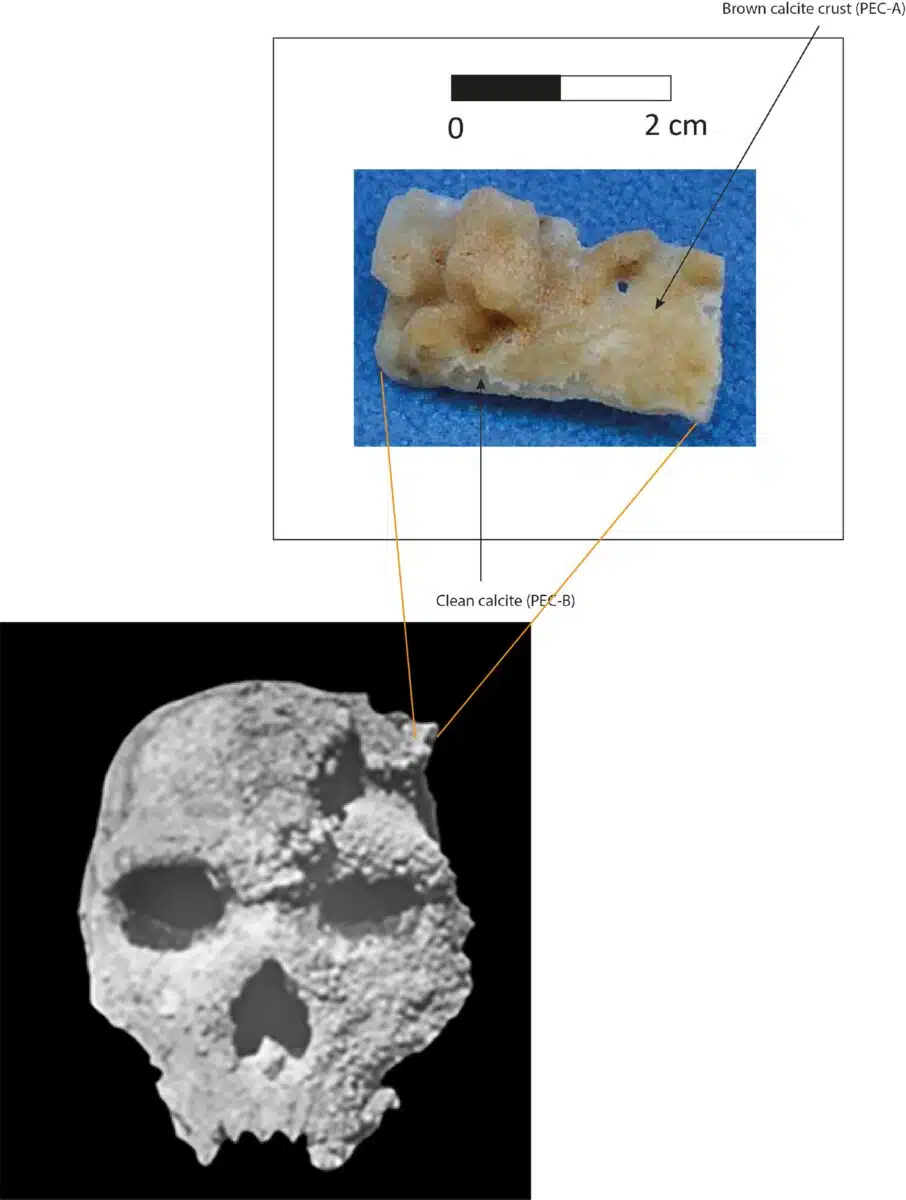

The calcite that sealed the skull to the Mausoleum chamber wall also preserved the key to its age. Uranium-series dating measures the decay of trace uranium trapped in calcite as it crystallizes from groundwater. The method works because calcite incorporates uranium but excludes thorium at formation, allowing researchers to calculate when precipitation occurred.

The new U-series dates on the Petralona cranium published in the Journal of Human Evolution analyzed samples from the calcite encrustation on the skull. The results produced an age of 286,000 years with a margin of error of 9,000 years, meaning the calcite formed approximately 286,000 years before present. Because the calcite grew on top of the bone, the skull itself must be at least that old.

The study states: “the results yield a finite age suggesting that the Petralona cranium has a minimum age of 286 ± 9 ka.” Co author Chris Stringer of the Natural History Museum in London explained to Live Science that the skull is likely close to 300,000 years old, noting that “it likely didn’t take long for the skull to acquire its first layer of calcite.”

This precision ends decades of conflicting estimates. Previous attempts using electron spin resonance had produced ages scattered across the Middle Pleistocene. The new mass spectrometry measurements required only milligram sized samples, allowing analysis of the thin crust directly adhering to the bone.

A Distinct Population

The Petralona individual was almost certainly male based on skull size and robustness, with moderate tooth wear indicating young adult age at death. But its features fit no simple category. The specimen exhibits a massive brow ridge, low braincase, and broad facial structure that distinguish it from both modern humans and classic Neanderthals.

Stringer told Live Science that “the Petralona fossil is distinct from H. sapiens and Neanderthals.” He and his colleagues place it in Homo heidelbergensis, a species first named from a jawbone found near Heidelberg, Germany in 1908. According to the Smithsonian Institution’s Human Origins Program, Homo heidelbergensis lived from about 700,000 to 200,000 years ago in Africa and Europe, with a larger braincase than older species but retaining a very large browridge.

The Petralona skull’s closest morphological match sits 6,000 kilometers away. Stringer and colleagues have long noted its resemblance to the Kabwe cranium from Zambia, which a 2020 study in Nature redated to approximately 299,000 years ago. The journal article notes that “numerous studies have shown its close morphological and phenetic resemblance to the Kabwe cranium from Zambia.”

The similar ages of the two specimens, now separated by only about 13,000 years, strengthen arguments for a widespread population spanning the Mediterranean and southern Africa during the Middle Pleistocene.

Coexistence in Europe

The new age estimate places the Petralona population in Europe at the same time Neanderthal features were already emerging elsewhere on the continent. Fossils from the Sima de los Huesos site in northern Spain, dated to approximately 430,000 years ago, show derived Neanderthal characteristics, meaning the two lineages overlapped in time for more than 100,000 years.

The Journal of Human Evolution study states that “the new age estimate provides further support for the coexistence of this population alongside the evolving Neanderthal lineage in the later Middle Pleistocene of Europe.” Stringer elaborated to Live Science that the finding supports “the persistence and coexistence of this population alongside the evolving Neanderthal lineage.”

Whether these coexisting groups remained biologically separate or occasionally interbred remains unknown. Later Neanderthals and modern humans are known to have interbred based on genomic evidence, but no DNA survives from specimens this old in warm climates.

The Smithsonian Institution notes that comparison of Neanderthal and modern human DNA suggests the two lineages diverged from a common ancestor, most likely Homo heidelbergensis, sometime between 350,000 and 400,000 years ago.

Ongoing Taxonomic Debate

Whether Homo heidelbergensis represents a valid biological species or an informal grouping of Middle Pleistocene fossils continues to divide paleoanthropologists. Some researchers advocate splitting the European and African specimens into separate species, while others maintain the extended hypodigm captures genuine evolutionary relationships.

The journal article acknowledges this debate directly: “There is currently much debate about the validity of the extended hypodigm H. heidelbergensis sensu lato and the evolutionary position of the associated fossils, particularly whether any of them might have been ancestral to H. sapiens or to H. neanderthalensis, ancestral to both, or ancestral to neither.”

The Petralona cranium’s secure age gives researchers a fixed point for assessing other European fossils from the same interval. But the fossil itself provides only anatomical evidence, not behavioral. No artifacts can be reliably linked to the Petralona individual, so researchers cannot say whether this population shared the large game hunting and shelter building documented at other Homo heidelbergensis sites.

First Appeared on

Source link

Leave feedback about this